- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- June 2016 - Volume 84

- Indonesians in Mindanao

FOCUS June 2016 Volume 84

Indonesians in Mindanao

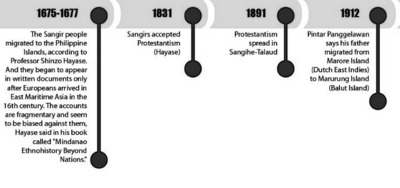

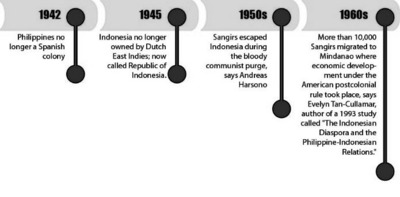

Recorded migration of Indonesians to Philippine shores dates back to the 17th century,1 with the first major wave of diaspora occurring in the early 1900s.2 Porous maritime borders and proximity of the coasts of Mindanao led many Indonesians belonging to the Sangir and Marore groups from North Sulawesi in Indonesia to move to Balut and Saranggani Islands of Davao del Sur province. Socio-cultural similarities with the ethnic communities of Mindanao including ethnolinguistic linkages and family and social networks strengthened the development of “transnational” communities in many parts of Mindanao at that time.3

Timeline of Migration of Indonesians to the Philippines4

Studies identified several push and pull factors of the first wave of Indonesian migrants including: (1) the Dutch presence and rule in their homeland; (2) overpopulation; (3) scarce resources and (4) other economic hardships.5

Studies identified several push and pull factors of the first wave of Indonesian migrants including: (1) the Dutch presence and rule in their homeland; (2) overpopulation; (3) scarce resources and (4) other economic hardships.5

The descendants of these Indonesian migrants (also identified as Persons of Indonesian Descent [PIDs]) currently reside in the provinces of Davao del Sur, Davao del Norte, Davao Oriental, Saranggani, Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato, and South Cotabato, and the cities of General Santos and Davao.6

The stance of an Indonesian whose parents came to Mindanao in the 1930s but who neither spoke the Indonesian language nor knew relatives in Indonesia, is probably true of many other Indonesians in the region. They maintain their identity as Indonesians but call the Philippines their home.7

At Risk of Being Stateless

Indonesian law puts these Indonesians at risk of becoming stateless. The 1958 Law Number 62 on the Citizenship of the Republic of Indonesia8 provided that Indonesian citizenship would be lost upon failure to declare intention to retain citizenship within five years of living outside Indonesia. The 2006 Indonesian citizenship law9 retained the same rule but allowed reacquisition of Indonesian citizenship. However, citizenship reacquisition should be done within three years from the promulgation of the 2006 law.10

Indonesian citizenship is also lost due to possession of foreign passport, travel document, or national identification cards.11 Today, many of the Indonesians living in Mindanao possess Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) identification card, a Philippine government-issued document. Although only Filipinos are supposed to have these cards, the Indonesians are able to get the PhilHealth cards because of lenient processing procedures.

Voluntary participation in a foreign election is also a ground for losing Indonesian citizenship.12 While the right to vote in Philippine elections is exclusive to Filipino citizens, many Indonesians have registered as voters with the Philippine Commission on Elections (COMELEC) and have participated in elections.

With very little access to information about their rights and little or no financial resources,13 many Indonesians have failed to comply with the requirements in retaining Indonesian citizenship or in reacquiring it, leaving their legal status in limbo. Without nationality, they cannot enjoy their human rights, including: the right to freedom of movement; formal education; access to social services; and own property. They often have poor access to basic services like affordable healthcare and higher education.14

Community Profile

In 2012, PASALI Philippines Foundation, Inc., with the support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), released a mapping report on the Indonesians in Mindanao.15 Researchers visited eleven communities in Saranggani, Sultan Kudarat, Davao del Sur provinces and General Santos City. Only a few of the original migrants were left. The majority of the respondents in the mapping exercise were second- and third-generation Indonesians. Most of them resided along the seashore and relied on subsistence fishing or farming in order to provide for their family’s daily consumption needs.

Since foreigners are prohibited from owning land in the country by the 1987 Philippine Constitution, the Indonesians cannot own the land where their houses sit. They constantly face risks of sudden eviction by Filipino land owners who can withdraw the permission to use the land at any moment.

Registration

Since 1990, the Indonesians have been encouraged to formally register with the Philippine immigration authorities. Philippine immigration regulations require all foreigners who stay in the country for more than fifty-nine days to secure an Alien Certificate of Registration (ACR), which is renewable annually. The 2012 PASALI report however revealed that a majority of the Indonesian respondents remained unregistered.

The Indonesian respondents have difficulty complying with the registration requirement as it is cost prohibitive. As of 2014, first-time registration and renewal of the ACR costs sixty US dollars for migrants who were fourteen years and older. The government also imposes a penalty for non-renewal. While the fee is a small amount, expenses to be incurred in order to successfully obtain the ACR are considerable. The person must personally appear at the immigration office to be able to register. The transportation cost of an entire family, with multiple boat rides, would amount to around twenty US dollars. While some choose to abide by the rules, many Indonesians voiced out that the costs were too much of a burden given that the family income was insufficient to sustain their basic needs. There are even cases where the ACR expenses are more than the combined yearly income by a family of twelve persons.16 Also, those who do not have the necessary documents are discouraged from even applying for an ACR.

Failure to comply with the registration requirement could mean detention and deportation.

Livelihood

Aside from the struggle of securing an ACR, the Indonesian respondents also face difficulties in obtaining work permits. Philippine labor laws require foreigners who want to engage in gainful employment to secure an Alien Employment Permit (AEP). In addition, employment opportunities usually require them to present documents to prove that they are legitimately staying in the country and/or have high educational attainment, which most Indonesians residing in Mindanao lack.

Many of the Indonesian respondents have no stable source of income. They are employed in seasonal work in coconut plantations, rice and vegetable fields, and fishing enterprises that are owned by Filipinos. Due to limited job opportunities, the average household family income of the Indonesian respondents ranged from twenty US dollars to seventy-five US dollars per month. Others who reside in urban areas have a higher average income.

Basic Living Conditions and Access to State Services

The majority of the Indonesian respondents have very poor living conditions. A typical Indonesian family household would not have basic facilities such as a water supply and a toilet. Because of low income, they constantly experience problems of food and water security.

Philippine public primary and secondary schools accept all children regardless of their citizenship. However, Indonesian families worry about expenses for transportation, school supplies, project materials and food while in school. Despite having relative access to education, a big number still consider themselves illiterate, especially those belonging to the older generations. Due to financial difficulties, fewer Indonesians opt to continue their education, as seen in the decreasing number of college students. Even those Indonesians who have obtained college degrees ultimately experience challenges in finding stable employment because of their uncertain residence status.

Basic medical and health services provided by public hospitals and health centers (including the national health insurance program or Philhealth) are easily accessible to Indonesians who reside in urban areas. However, many of them live in far-flung areas and have difficulty accessing these services. Many Indonesians who avail of Philhealth benefits are married to Filipinos.

The Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), the conditional cash transfer program of the Philippine government, has also been made available to the Indonesians. Again, there is a disparity between those who live in the urban and the far-flung areas. Those who live farther from the 4Ps centers are discouraged from obtaining 4Ps benefits due to the transportation expense in using motorized boats to get there.

One report shows Indonesians recognizing the assistance provided by the Philippine government (such as supply of medicines and mosquito nets), while lamenting the lack of assistance from the Indonesian government.17

Recent Developments

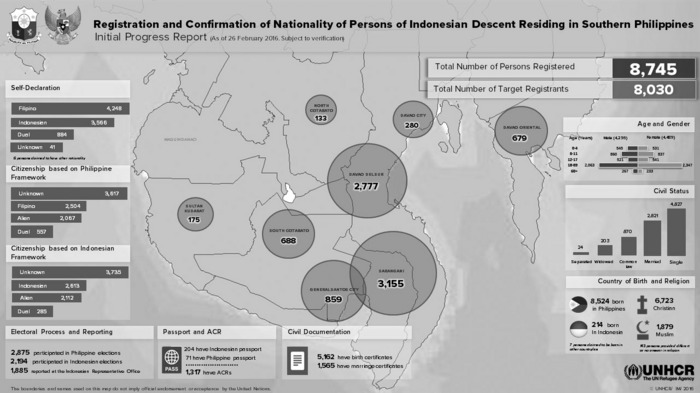

The Philippine and Indonesian governments jointly committed in 2012 to take action in addressing the situation of the Indonesians. As part of the UNHCR’s #IBelong campaign that aims to end statelessness worldwide by 2024, the Philippines’ Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Indonesian Consulate in Davao city, with the assistance of the Philippine Public Attorney’s Office (PAO) and the Bureau of Immigration (BI), started the registration process of the Indonesians. The registration process yielded 8,745 Indonesians in seven provinces and two cities, which include the provinces of Davao del Sur, Davao del Norte, Davao Oriental, Sarangani, Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato, South Cotabato, and the cities of General Santos City and Davao.18 Out of this number, six hundred sixty-four underwent, in March 2016, the citizenship formalization process led by the two governments. The UNHCR said that five hundred thirty-six persons of Indonesian-descent have been confirmed as Filipinos, with the rest opting to remain Indonesian.19

Despite this groundbreaking initiative, challenges remain. Those who are eligible to undergo the Philippine naturalization process are required to pay a fee of around 2,100 US dollars, as mandated by law. Considering their current socioeconomic status as discussed above, it would be impossible for them to afford such extravagant fee. The UNHCR Philippines is currently in talks with the Philippine government to consider exempting them from the naturalization and immigration fees. There are also plans to ask legislators from the provinces where the Indonesians reside to sponsor a law that would grant Filipino citizenship to these applicants and spare them from such a heavy burden.20

There is still much work to do to resolve the problem of statelessness of the Indonesians. But as seen in their experience, a lot can be done with the involvement and strong commitment of state agents, civil society and other stakeholders who all have a shared vision.

Anne Maureen B. Manigbas is a lawyer and the Director for Internship at the Ateneo Human Rights Center.

For further information, please contact: Anne Maureen B. Manigbas, Ateneo Human Rights Center, G/F Ateneo Professional Schools Building, 20 Rockwell Drive, Rockwell Center, 1200 Makati City, Philippines; ph (632) 8997691 local 2109; ph/fax: (632) 8994342; e-mail: ahrc.law@ateneo.edu; http://ahrc.org.ph/.

Endnotes

1 Inday Espina-Varona, “Indonesians emerge from legal limbo in the Philippines,” Union of Catholic Asian News, 16 March 2016, available at www.ucanews.com/news/indonesians-emerge-from-legal-limbo-in-the-philippines/75505 (last visited 26 May 2016) and Rolando Talampas, “Indonesian Diaspora Identity Construction in Southern Mindanao Border Crossing,” Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspective on Asia, V52 No. 1, 2015, page 65, full text available at www.asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-51-1-2015/Indonesian%20Diaspora%20Identity%20Construction%20in%20a%20Southern%20Mindanao%20Border%20Crossing.pdf (last visited 16 June 2016).

2 Virginia A. Miralao & Makil Lorna Peña-Reyes, Exploring Transnational Communities in the Philippines, Philippine Migration Research Network (PMRN) and Philippine Social Science Council (Quezon city: PSSC, 2007), page 18.

3 Ibid., pages 18-19.

4 Mick Jethro Basa, Life Along The Borders: The Indonesian Sangris on Balut Island, Konrad Adenauer Asian Center for Journalism at The Ateneo De Manila University, available at http://acfj.ateneo.edu/life-along-the-borders/ (last visited 23 May 2016).

5 Supra note 1, Talampas, page 65.

6 Supra note 1.

7 Vivian Tan, Statelessness in the Philippines: Indonesian descendants feel torn between two lands, UNHCR, 15 September 2014, available at www.unhcr.org/5416d3519.html (last visited 1 June 2016).

8 Law No. 62 of 1958, Law on the Citizenship of the Republic of Indonesia, 1 August 1958.

9 Law of the Republic of Indonesia No. 12 on Citizenship of the Republic of Indonesia, 1 August 2006. This law repealed the 1958 citizenship law.

10 Ibid., article 42.

11 Ibid., article 23 (h).

12 Ibid., article 23 (g).

13 Supra, note 1.

14 “Hundreds finally out of legal limbo in groundbreaking pilot between Indonesia, the Philippines,” UNHCR Philippines Press Release, 10 March 2016, http://unhcr.ph/news-stories/hundreds-finally-out-of-legal-limbo-in-groundbreaking-pilot-between-indonesia-the-philippines (last visited 16 June 2016).

15 PASALI Philippines Foundation, Inc., Persons of Indonesian Descent in Mindanao, Philippines, Periodic Report, 2012. Full report available at https://issuu.com/manchamancha/docs/mapping_indonesians_pasali_philippines_unhcr.

16 See the 2012 Pasali report for an example of this situation on page 15.

17 Supra, note 4.

18 Supra, note 14.

19 Carolyn O. Arguillas, “664 persons of Indonesian Descent (PIDs) in Mindanao end statelessness,” MINDANEWS, 14 March 2016, available at www.mindanews.com/top-stories/2016/03/14/664-persons-of-indonesian-descent-pids-in-mindanao-end-statelessness/ (last visited 28 May 2016).

20 Supra, note 1.