Overview: Human Rights Centers in the Asia-Pacific

The HURIGHTS OSAKA Directory of Human Rights Centers in the Asia-Pacific1 defines a human rights center as an

institution engaged in gathering and dissemination of information related to human rights. The information refers to the international human rights instruments, documents of the United Nations human rights bodies, reports on human rights situations, analyses of human rights issues, human rights programs and activities, and other human rights-related information that are relevant to the needs of the communities in the Asia-Pacific.2

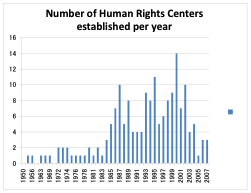

Establishment of Human Rights Centers

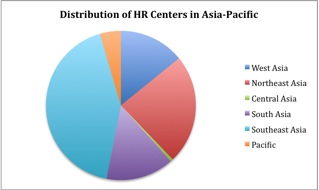

By 2008, around two hundred human rights centers have been existing in at least seventeen countries in Asia-Pacific. Japan, Sri Lanka, India, Australia, and the Philippines have several centers of various types operating for at least fifteen years. The oldest center (established in 1951) is in India, focusing on research on marginalized groups, followed by a center established in 1968 in Japan with discrimination against socially-outcasted Japanese as the major focus of research.

It took more than a decade for a few more centers to be established. In Sri Lanka, where the first regional workshop on human rights mechanism was organized by the United Nations in 1982, two centers were already established by 1983. Toward the middle part of the decade of the 1980s, centers in Australia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand followed.

The decade of the 1990s saw the establishment of many more centers including those in South Korea, China, Vietnam and New Zealand.

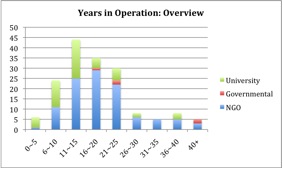

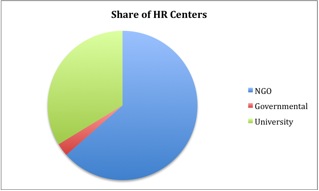

These human rights centers are generally categorized into non-governmental, government-supported and university-based institutions.

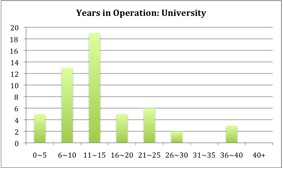

A significant number of these centers are university-based, and many of them are affiliated with law-schools. Their research programs cater primarily to the needs of their respective academic communities. A few however have either national or "regional" outreach programs - reaching out to institutions in other parts of the country or working at the Asia-Pacific level. The Ministry of Law and Human Rights in Indonesia initiated a unique initiative of establishing "PUSHAMs," short name for Pusat Studi Hak Asasi Manusia (Center for Human Rights Studies) in many state and private universities (particularly in the law faculties) in the country. A non-governmental organization initiative on child rights led to the establishment of Child Rights Centers in universities and colleges in Bangladesh, India and Nepal.3 A regional office of the Philippine Commission on Human Rights initiated the establishment of provincial and city human rights education centers in the local colleges and universities to be able to serve the needs of the local communities as much as their respective academic communities.4 In a pattern similar to the initiative of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights in Indonesia and the regional office of the Philippine Commission of Human Rights, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK) has been entering into memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with Korean universities since 2006 for the establishment of human rights centers that would make universities the regional hubs on human rights. As of early 2012, ten universities have MOUs with the NHRCK. The MOUs highlight the following objectives:5

- Elevate the role of regional hub universities through human rights education and research

- Increase cooperation between NHRCK and the universities in carrying out human rights education

- Establish collaboration between them in researching human rights issues in the local community

- Increase human rights materials exchange

- Increase human resources exchange

- Implement student internship programs for law school students specializing in human rights law.

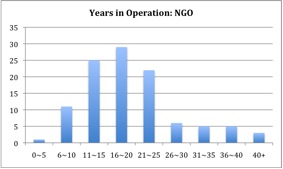

Almost half of the centers identified (2008 data) are non-governmental institutions. They focus on specific issues such as discrimination against women, rights of minorities, or on concrete action such as policy and legal reform advocacy, and monitoring of human rights situation.

Government-supported centers constitute the third major category of the centers. They do research as part of the public information function, publish human rights materials, and also undertake human rights education activities.

Some university-based centers support human rights education in schools programs.6

Over-all, these centers are doing significant amount of work in their respective fields of interest. There is an enormous amount of published research work, materials for human rights education, and systems for information dissemination. But their activities are largely unknown beyond national borders or networks. This limits the dissemination to, and use of research output by, a much wider audience.

A few of these centers have established linkages among themselves or with other institutions doing joint research projects and taking part in other activities such as workshops in human rights education or campaigns. But these linkages hardly create a regional community of human rights research centers. They are not identified as human rights institutions with their own identity separate from non-governmental organizations doing human rights protection and campaign work, or from the national human rights institutions.

In many countries, governments, NGOs and national institutions collaborate in undertaking projects on human rights education in schools. This collaboration is proving to be an effective means of maximizing competencies - the governments (through their educators) provide the education expertise while NGOs and to a certain extent the national institutions and human rights centers provide their experience in human rights work or supply information or materials on human rights.

Characteristics and Functions

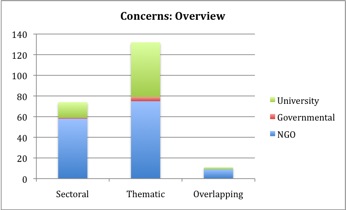

The human rights centers of Asia-Pacific share some common as well as unique characteristics. They share the need to do research, which in many cases relate to very particular issues. They therefore focus on certain concerns:

- sectoral ? women, indigenous peoples, minorities, etc.

- thematic ? human rights violations, particular rights (right to development, housing rights), larger issues (armed conflict situation/peace, development, democracy, etc.)

- overlapping concerns ? human rights and democracy, human rights and peace, human rights and environment, etc.

They also share the view that they need to make their information useful to the public by becoming known as resource center/documentation center/library/database center/information center/research institute. As such they are meant to

- disseminate information on international human rights standards and mechanisms, relevant local laws and processes

- expose human rights issues and encourage public discussion

- analyze measures (international and national) towards human rights protection, promotion, realization, and propose new measures (in terms of proposed laws, policies, programs, particular actions).

A few human rights centers express what others imply as far as their identity is concerned. A number of human rights centers introduce themselves as "non-partisan, independent" institutions. This can mean maintaining independence from the "government, all political parties, corporations, and other interest groups" and fighting for "all people without regard for class, race, gender, religion, or nationality."7

The functions of these human rights centers can be generally classified into the following:

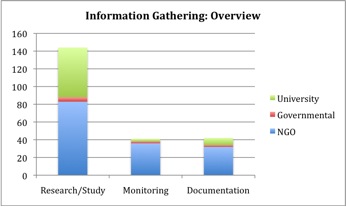

a) Gathering information can be in the form of any of the following activities:

- Research

- Study

- Fact-finding

- Monitoring

- Investigation

- Documentation

- Data analysis.

One human rights center notes that digitized data

widens the scope ... and size of its data collection and helps identify trends and changes, helps in filing class-action suits, organizes based on taluka or district to effectively raise a particular issue, helps lobby at the international level, and provides a replicable model for other organizations around India.8

The human rights centers normally have a database of information collected through various means ranging from formal research to informal data-gathering (such as community-based projects like the "Shooting Back" project of B'tselem on making video documentation of ground situations, and that of Burma Issues project on training village-level documentalists). The database of information becomes the basis of many activities being undertaken, and also of annual reports on human rights situation (very important outputs of the centers).

b) Dissemination of information that is meant for

- policy review and lobby for policy recommendations

- advocacy/campaign for human rights protection (urgent appeals for example)

- education, awareness-raising.

The dissemination of information generally takes the form of a "research and advocacy approach" and/or "research and education approach." These approaches ensure the practical and pro-active use of the information gathered in addition to developing information base for general public use.

The information can be in the form of formal publications (books), reports on current human rights situations, as well as educational materials. Some human rights centers produce audio-visual materials such as videos and other teaching and learning materials.

One center lists the uses of its studies as:

- Advocacy material

- Means to raise the visibility of Dalit rights

- Means to assess new area of rights violations

- Means to explore new area of intervention according to socio-economic changes

- Basis for the strategic interventions

- Means to sensitize the civil society

- Means to ensure a clear perspective while monitoring the violations.

Through these uses of information, human rights centers advocate change using arguments based on research and proper analysis of the situation.

Though not exclusively their function, some human rights centers combine service delivery (legal aid, rehabilitation, training, etc,) with advocacy/campaign, and other activities.

University-based human rights centers offer curricular and extra-curricular courses on human rights (tertiary and graduate levels) as well as community education programs.

Resources

The human rights centers in the Asia-Pacific generally produce materials that inform ordinary people of human rights issues, relevant laws, mechanisms to enforce/protect/realize human rights, as well as materials for teaching and learning them. The centers have a variety of materials such as the following:

- Newsletters

- Annual reports (usually reports on the general human rights situation)

- Special reports (focused on specific issues or incidents)

- Reports on human rights activities

- Practical guides on using international human rights instruments and their application in domestic legal systems (manuals, training pamphlets, etc.)

- Teaching and learning materials (lesson plans, training modules, Q & A pamphlets, comic books, etc.)

- Audio-visual materials (including documentaries and easy-to-understand introductory materials on particular human rights)

- Translation of human rights documents from the United Nations and other institutions.

Government-supported centers have also the capacity to access materials and information that are available in government agencies such as the government human rights policies, programs and projects; reports on human rights situations; informative materials on human rights issued for public use (such as pamphlets on domestic violence or child abuse or facilities for the aged or persons with disabilities).

The human rights centers (specially NGO-based and university-based) provide human resources who can perform a variety of tasks from human rights education, to helping implement community projects (such as research on particular human rights issues), to advocacy work.

The centers also provide human rights materials (including research reports and teaching and learning materials) that are needed in human rights work.

Conclusion

The human rights centers are still in many ways at the developing stage. Yet they have already been providing service to the community through information dissemination, and education activities. They suffer from limited resources, and for those supported with government funds the possibility of budget cut-off. They also have limitation as far as reaching communities particularly those in need of support.

Human rights centers in the Asia-Pacific deserve to be recognized as a human rights player on its own account, whose role is much needed in protecting, promoting and realizing human rights.

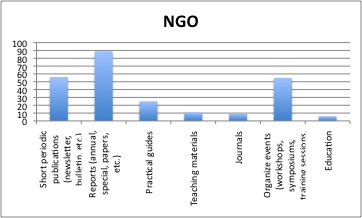

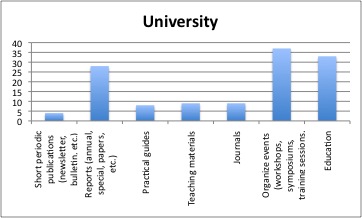

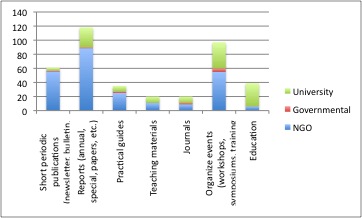

This article benefited from the assistance of Ms. Erika Calazans, a HURIGHTS OSAKA intern in the summer of 2009, who created the graphs based on the data of the 2008 Directory of Asia-Pacific Human Rights Centers (Osaka: HURIGHTS OSAKA, 2008). Mr. Adrian Bonifacio, a HURIGHTS OSAKA intern in the summer of 2011, provided additional graphs, particularly on characteristics, functions and resources of the human rights centers.

ENDNOTES

1. Published in 2008 but its longer and updated center profile version is available online: http://hurights.pbworks.com.

2. See the Directory of Asia-Pacific Human Rights Centers (Osaka: HURIGHTS OSAKA, 2008), page 4.

3. See Save the Children Sweden, "Building Partnerships with Academia to Further Child Rights in Higher Education in South Asia" in Human Rights Education in Asian Schools 11/151-166.

4. See Anita M. Chauhan, "Center for Human Rights Education: Philippines" in Human Rights Education in Asian Schools 10/107-125.

5. "Ewha, Korea University Join the Effort for Human Rights [2007-12-03]," National Human Rights Commission of Korea, www.humanrights.go.kr/english/activities/view_01.jsp

6. The Center for the Study of Human Rights of the University of Colombo in Sri Lanka is an example of university-based center. It has been implementing for many years now human rights education programs in a number of schools. It has been working with Sri Lankan NGOs and other institutions.

7. See Principles of TAHR in www.tahr.org.tw/index.php/article/2004/06/28/309/

8. See profile of Navsarjan in the Directory of Human Rights Centers in the Asia-Pacific, page 52, also in http://hurights.pbworks.com/India+Centers#Navsarjan.