- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- September 2001 - Volume 25

- Child Labor and India's Football-making Industry*

FOCUS September 2001 Volume 25

Child Labor and India's Football-making Industry*

India is the world's second (following Pakistan) largest producer of footballs and other inflatable balls. Between April 1999 and February 2000, India's production reached almost US$ 18 million (Rs. 7,854. 76 lakhs). 1 United Kingdom imported a total of US$ 6. 86 million for the same period. 2 Other important European importing countries are France, Germany, Spain, Italy and The Netherlands. Besides inflatable balls, badminton rackets, shuttle cocks, cricket balls and bats, hockey sticks and different kinds of gloves and protective equipment are also manufactured. There are 364 sports goods exporters registered with the Sports Goods Export Promotion Council (SGEPC) in India.

According to the Sports Goods Manufacturers and Exporter's Association in India, the total number of persons working in the industry is about 30,000. A report by Christian Aid however gives a figure of around 300,000 people working in the industry, "either in the 1,500 factories and smaller manufacturing units or as subcontracted home-workers". 3

It is not fully clear how this large difference can be explained, but it can be assumed that the former figure does not include the home-based workers who are working for the manufacturers/exporters via the contractors. The number of home-based workers can only be roughly estimated as there are no reliable data on them yet. If the figure of 300,000 is correct this would mean that nine out of ten workers in the sports goods industry are in the informal, unorganized sector.

The V. V. Giri National Labour Institute of India (NLI), as commissioned in 1997 by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, studied the child labor situation in the Indian sports industry. Its report gives a detailed account of the child labor issue. 4 Being the most comprehensive survey on the issue thus far, although only limited to the Jalandhar area, 5 the report estimates that about ten thousand children are working in sports goods production. Of these about 1,350 are only working (and not going to school) while the rest are both working and school going. While 92% of the working children are stitching footballs, 8% of the child laborers in Jalandhar and its surrounding villages make other sports goods such as shin pads, cricket balls, rackets and shuttles. 6

The report makes a distinction between children who are only working (OW) and not going to school, children who are working and school going (WSG), children who are only school going (OSG) - although they might be doing households chores - and not working and not school going children (NWNSG).

The survey found that three out of four families reported children who are either only working or combining education with work.

Footballs are stitched by children from five years and older. However, 'only' 11% of the OW children are between five and nine, while 26% are between ten and twelve. The rest (63%) are thirteen or fourteen years old. Two-thirds of the WSG children are between five and twelve, indicating that most children start to stitch footballs when they are quite young. The work participation of boys and girls in stitching balls is almost the same.

The work intensity of the stitching children is high. A six-year-old 'only working child' spends on average seven and a half-hours stitching balls, while a thirteen-year-old child spends nine hours of work. Children who go to school and work have to shoulder a bigger work burden: nine hours when they are six and almost eleven hours when they are thirteen. It is also striking that a quarter of the OW children work at night, while 14% of the WSG children do so.

Most children leave school from ten years of age onwards. There is a relatively high rate of school attendance of children between five and nine years old. However, with the average number of working hours (besides school work) being more than three hours each day after the age of ten, the pressure builds up to leave school: "The work pressure finally leads to dropping out of school. The data suggests that 90% of drop-outs have turned into full-time workers. 7 The NLI report states that more than half of the respondents say that financial problems or the need to assist in family work forced the children to leave school and start working full-time. More than a quarter of the respondents reported lack of interest in school as the main reason for dropping out. The NLI report sums up the impact of child work on education as follows: "Child work renders school education futile in the perception of both parents and children. Parents do not insist and children lose interest. .8

There are many factors to consider in this issue. The quality of schooling combined with the lack of school-going tradition (especially for girls), the pressure of work once started and the fact that most stitchers are socially discriminated 'Dalits' might ultimately be more important than the often, and perhaps more easily voiced, financial reasons to drop out. 9

Earning money is not the only reason why children are working. Even in the lowest income category children go to school, while at the same time there is a very high incidence (67% or more) of child labor in the households earning more than Rs. 600 per capita per month. The NLI report concludes: "Though income may be an important condition for a household to make the child work, it is not the essential condition. .. on the part of the family to involve children in wage employment. "

According to representatives of the sports goods industry, the problem of child labor has been substantially reduced since the research was done by the NLI. In 1998, sports goods exporters formed the Sport Goods Foundation of India (SGFI). It now has thirty-two members. The members contribute 0. 25% of their earnings from manufacturing footballs to support an inspection and child labor rehabilitation program. 10 Mr. S. Wasan, the SGFI secretary, said that the foundation expected an external monitoring group (Societe Generale de Surveillance or SGS) to find only a few working children, because of the increased awareness on the issue. 11 This expectation is not surprising because SGS found only one child after the first round of monitoring almost 200 stitching locations. 12 and 70 children after covering almost 75% of the stitching locations in June 2001. 13 Another SGFI official felt that the problem is now much less compared to two years ago. He particularly expected the number of 'only working children' to be very small now. 14

Sangal Sole Colony in Jalandhar and surrounding areas.15

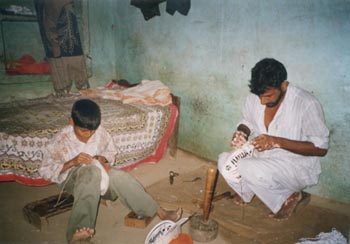

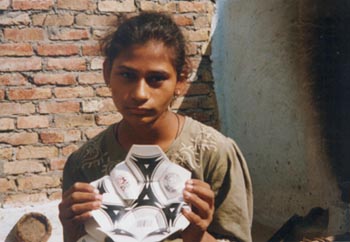

"A mother and daughter are stitching the 32 separate panels of a football together. For a long working day of twelve hours they earn around Rs. 35. Two girls of around 15 or 16 years together stitch three or four balls a day and earn Rs. 15 a ball. 'This is the general picture' according to Mr. Jai Singh, coordinator of Volunteers for Social Justice, an NGO based in Punjab. Two young women tell us that they stitch four balls a day and together earn Rs. 60. A boy and his father also tell us they earn roughly Rs. 30 a day each.

During the time of the visit, several children, varying in age from approximately ten to fifteen years, were assembling footballs. At that time however children are not massively at work. At busy times, when orders pour in, the picture is very different. 'It's off season now, so relatively few children are engaged', tells Singh. Many inhabitants confirm this statement. But apparently there is something to hide even during off-season. Just after meeting a contractor, he rushed off on his scooter to the next village to warn the people about 'unexpected guests'. Everywhere doors were being closed.

Other villages around Jalandhar and Batala16 do not instill the same kind of optimism prevalent in SGFI. Awareness that child labor is not to be employed in the industry seemed to result mainly in children hiding or running away as soon as they, their family members or their neighbors spot outsiders.

In the April 2000 visit, most adults in villages admitted straight away that children also stitch footballs. Some contractors did the same. They felt that little can be done about it because of the poverty of the families concerned. Asked if they received instructions from their company on avoiding child labor, they answered no. 17

Visits to, among other places, Sangal Sole Colony in Jalandhar and Gandhi Camp in Batala further reinforced our impression that the conclusions of the NLI report are still valid to a large extent. In fact the number of stitching children in Punjab might be much larger than 10,000.

Legal work

Football stitching by children, at whatever age, is not illegal. The Indian Child Labour (Prohibition & Regulation) Act of 1986, which bans child labor in certain hazardous industries or occupations like carpet weaving or matchmaking, does not consider stitching of footballs a hazardous occupation for children. But even if it did, it still would not affect child labor in the football industry since the law allows homework in all occupations, without any restrictions.

Almost five years ago FIFA agreed on a 'Code of Labour Practice' with the International Federation of Trade Unions (ICFTU) for FIFA licensed products, particularly footballs. The code however was never signed or implemented. Instead, programs in Pakistan and recently in India were started to eradicate child labor from the industry. In addition, the contracts signed by the football importing companies with FIFA. 18 contain clauses on labor conditions that are based on the Code of Conduct of the World Federation of Sporting Goods Industry. These clauses are less stringent than those in 'the original FIFA Code'. For example, provision on 'fair wages' is missing. Even these contracts however are violated in India on several points. 19

Concluding statement

The SGFI and its Steering Committee, in consultation with local communities, NGOs, unions and others, should find ways to implement the important conclusion of the NLI report. It is recommended that the contractor system be replaced by a system with effective monitoring and regulation by the State, employers and trade unions. In addition, the idea to form labor co-operatives should be further studied, and implemented with the help of NGOs and unions.

Bringing an end to the use of child labor and guaranteeing basic labor rights in the sports goods industry of course go beyond the influence of FIFA and other football associations. Therefore all companies, regardless of their relation to FIFA, should have a code of labor practice which is at least as good as the original FIFA Code and is independently monitored and verified.

For further information, please contact: India Committee of the Netherlands, Mariaplaats 4 3511 LH Utrecht, The Netherlands, ph 00-31-30-2321340; fax 00-31-30-2322246; e-mail: liw@antenna. nl; website: www. antenna. nl/liw

Endnotes

- Forty-seven Indian rupees are roughly equivalent to one US dollar.

- Figures from the Sport Goods Export Promotion Council, New Delhi. Other important importers of Indian inflatable balls, mainly footballs, are Australia (Rs. 98 million), France (Rs. 52 million), South Africa (Rs. 51 million), Germany (Rs. 43 million), USA (Rs. 41 million), Italy (Rs. 38 million), New Zealand (Rs. 24 million), Spain (Rs. 21 million) and The Netherlands (Rs. 20 million).

- Christian Aid, A sporting chance - Tackling child labour in India's sports goods industry, May 1997, page 3.

- V. V. Giri National Labour Institute, Child labour in the sports goods industry: Jalandhar, A Case Study, Noida, September 1998. This survey was jointly supported by FICCI and ILO-IPEC.

- Jalandhar is now the major center of India's sports goods industry. It is located in Punjab state. Other centers are Meerut in Uttar Pradesh and Gurgaon in Haryana. There is a traditional stitching community called Mahashak found in Jalandhar, Batala and Ludhiana in Punjab. It migrated from Sialkot in Pakistan during the partition between India and Pakistan in late 40s. Sialkot has traditionally been the center of sports goods industry.

- It can of course be questioned whether or not more than 30 villages and urban localities in Jalandhar area are involved in producing sports goods. Discussions between the NLI researchers and the trade unions led to the identification of 21 areas where there are large concentration of child labor for the sports goods industry. It was assumed that these areas constituted roughly 75% of the 'child labor' areas. A sample of 10 areas (five urban and five rural) out of 21, have a total of 2,993 households engaged in production of sports goods. Of these households, 1,292 were interviewed intensively. In total, 225 full-time and 1,492 part-time working children were found. Multiplying these figures by six brings the number of working children to 10,000.

- Child labour in the sports goods industry, op cit. , page xi.

- Child labour in the sports goods industry op cit. , page 42.

- This is supported by the experiences of MV Foundation in Andhra Pradesh which mainstreamed more than 100,000 poor rural children, including formally bonded children and girls, into formal education. Visit: www. antenna. nl/liw/index_e. html

- ''Missing goals", India Today, 9 July 2001.

- Interview with Mr. S. Wasan in magazine India Nu, May 2000.

- Sports Goods Foundation of India, The Realistic Approach(Part 2), 2000.

- "Missing goals," op cit.

- Interview with Mr. Purewal, manager of SGFI, April 2000.

- Report of visits by Mr. Jai Singh, Volunteers for Social Justice, and Gerard Oonk, India Committee of the Netherlands, April 2000.

- Report of Gerard Oonk, November 1999.

- Report of visits by Singh and Oonk, op. cit.

- The contracts were originally signed with International Sports and Leisure (ISL), the licensing company operating on behalf of FIFA. ISL went bankrupt in the early part of 2001.

- Press Report of the India Committee of the Netherlands, Utrecht, June 23, 2000, page 13.

*This is an edited excerpt of the report The Dark Side of Football: Child and adult labour in India's football industry and the role of FIFA (June 2000, India Committee of the Netherlands)" The full report is available at: www.indianet.nl/iv.html