- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- September 2010 - Volume 61

- Human Rights and the Osaka Prefectural Government

FOCUS September 2010 Volume 61

Human Rights and the Osaka Prefectural Government

The Kansai region of Japan has a long social movement history, particularly the anti- discrimination movements of the discriminated section of the Japanese population (so-called Buraku-min) and of the ethnic Korean residents (zainichi Koreans). At the time when a special measures law to eliminate the discrimination against the Buraku-min was in effect, the local governments in the region initiated programs and activities that implemented this law.

Osaka prefecture has one of the biggest Buraku-min communities in the country. It has one of the biggest communities of homeless people, and is home to about 25 percent of Japan’s roughly 600,000 people of Korean origin. Just like any other prefecture of Japan, it has its own share of people with disabilities and other disadvantaged groups.

Legal Measures

The Osaka Prefectural government adopted in 1947 special measures on the Buraku discrimination issue. These local measures were way ahead of the national measures started in 1969 to address Buraku discrimination under the Law on Special Measures for Dowa Projects. This 1969 law funded special projects in Buraku areas over a thirty-year period, and triggered local government programs on countering discrimination against the Buraku-min. In 1985, the Osaka prefectural legislative assembly enacted an ordinance regulating the investigation of personal backgrounds by private investigation agencies that lead to discrimination against the Buraku-min. In 1998, the Osaka prefectural legislative assembly enacted Ordinance number 42, “Creating a Society that Respects Human Rights,” as the general human rights policy for the prefecture.1 The policy upholds the universal principle of the human dignity of all human beings and supports the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Japanese Constitution. It states the obligation of the prefecture to promote human rights.

A 1996 ordinance regulating the disclosure by the prefectural government of personal information was amended in 2005 to provide more protection required under the 2003 Protection of Personal Information Act. While this ordinance applies to all persons, this is a vital measure in addressing Buraku discrimination.

Several prefectural policies came out in 2000s on human rights promotion. In 2000, the prefectural government adopted the Osaka 21st Century General Plan to Revitalize Osaka and Double Its Energy that defined Osaka's "vision for co- existence.” It aimed at having a ““society where everyone exerts the maximum [of] their potential, to make their own dreams come true” with “everyone respecting human rights and supporting one another.” In relation to foreign residents, the plan “aspires to create a community where the human rights of foreign nationals are respected, and in which individuals can exert their own characteristics, ethnicity and abilities without hesitation.”2

The Osaka prefectural government initially established in 1966 an office that focused on the Buraku discrimination issue. In 1992, a Human Rights and Peace Office was created within the then newly-created prefectural International Office. The Human Rights and Peace Office broadened its scope of work when it assumed responsibility for programs relating to peace, foreign residents and human rights promotion. In 1998, it was renamed Human Rights Office and placed in the Department of Planning and Coordination. In 2009, it became part of the Department of Civic and Cultural Affairs.

The Osaka Prefectural Human Rights Office

The current Human Rights Office aims to achieve the following major objectives:3

1. Promote an integrated approach to implementing human rights measures

2. Undertake human rights awareness activities

3. Plan for measures to promote peace

4. Enforce the ordinance on countering discrimination at the local communities

5. Implement integrated measures for foreign residents.

To achieve these objectives, the Human Rights Office has several groups assigned to undertake particular tasks or programs as in the following:

1. Management of human rights projects and other measures, holding of public hearings, and public dissemination on human rights;

2. Implementation of human rights education and awareness activities including development of teaching materials for human rights training and surveying public opinion on human rights;

3. Implementation of prefectural human rights ordinances, including monitoring of inquiries on personal information, implementation of program for foreign residents, awareness-raising activities on the ratified international human rights instruments, and administrative monitoring of HURIGHTS OSAKA;

4. Provision of human rights consultation and protection services, and coordination with other institutions providing similar services;

5. Support for the development of human rights policies; and liaison with similar offices in other prefectures, human rights movements, and the Osaka Prefectural Human Rights Association.

During the last few years the Human Rights Office produced the following materials:

1. Sozo - a human rights newsletter (issued twice a year)

2. Human rights information booklets (mostly in Japanese).

3. Humanite – annual human rights magazine that discusses various issues relating to women, aged, children, persons with disabilities, people living with HIV/AIDS, foreigners, workers, Burakumin, and North Korean abduction victims.

Humanite, a human rights magazine of the Osaka Prefecture

The Human Rights Office is the contact office for the overall coordination of prefectural human rights policies pertaining to the different departments within the prefectural government. Different prefectural offices deal with various human rights concerns such as those for homeless people, people with disabilities, children, women, and the aged. The Human Rights Office organizes meetings among relevant prefectural officials for this purpose. It also organizes the annual meeting of experts to discuss project proposals regarding foreign residents that can be implemented by the different prefectural offices in the following year.

Prefectural Activities

As part of its Plan of Action for the United Nations Decade for Human Rights Education (1997), the Human Rights Office has created, among other things, the Osaka Prefectural Basic Guidelines for the Promotion of Human Rights Policies (2001) and the Osaka Prefectural Plan for the Promotion of Human Rights Education (2005-2014).4 Through this work, the government focuses on children’s education, teaching the younger generations about, for example, respect for those who are different. However, there is still no mandated human rights education plan for public school students in Osaka prefecture. The Human Rights Office cited the difficulties of having such a plan for public secondary schools due to the busy schedule of Japanese students, who must concentrate on mathematics, Japanese, English and various other subjects and who often also attend juku, or cram schools, after their regular classes finish.5

As well, the national government in Tokyo is currently in the midst of its infamous jigyo shiwake (budget-cutting process). With the new coalition party in power and with a staggering public debt (the largest in the industrialized world), the national government is eyeing budget cuts to non-essential activities, and local governments could find human rights activities funding in peril. Previously, the national government worked on human rights issues mostly in the form of subsidies – for the construction of public facilities, housing, scholarships, etc. - to areas where human rights issues are particularly prominent, for example, Buraku areas.

Speakers of English, Korean, Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, Tagalog, and Thai have since 1993 been able to consult with the government in their own language through the Osaka Information Service for Foreign Residents. Municipal administrative and living information announcements over FM radio are also broadcast in Spanish, English, Korean, and Chinese and are also listed on the internet (but not in Spanish). Information in English and other languages on medical institutions in the Osaka area, where foreign languages are spoken, is available through multilingual guidebooks. Moreover, through its “Medical Information for Foreigners” websites in English, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese, one can find information on things like what to do in a medical emergency and how to navigate the health insurance system.

The Osaka prefectural government also subsidizes emergency medical institutions (but not hospitals) for the expenses they incur when uninsured foreign nationals need emergency care but cannot pay for it. This program is designed to allow everyone who needs emergency medical attention to receive it, whether or not they can afford health insurance. However, some elderly foreign residents or those with disabilities cannot gain access to this program.

Regarding housing rights, the Human Rights Office seeks to eradicate discrimination against minorities by real estate agencies and owners of rental houses by distributing booklets that raise awareness on housing rights. If a minority feels that he or she has been discriminated against when seeking housing, consultation services are offered, including in some foreign languages. The local government would then move to solve the problem “immediately and voluntarily,” though there is yet no law punishing acts of discrimination.

The Osaka prefectural government established in 1989 the Osaka Foundation of International Exchange (OFIX) “to promote the internationalization of Osaka, support and assist exchange activities of its citizens, contribute to the international community by improving services for foreign students, and to foster development in Osaka.”6 Foreigners living in Japan who have recently lost their jobs due to the global economic recession can go to OFIX and discuss (in English, Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, or Korean languages) their options regarding staying in the country.

Regarding women’s rights, acknowledging that women performing the same job as men receive only about sixty or sixty-five percent of the men’s salary, the prefectural government established a limited program to address the issue. The program does not provide financial support to working women to equalize their salaries to those of their male counterparts. The program also does not provide any special child-rearing support, such as daycare financial assistance or additional maternity leave. Local government programs in Osaka thus do little to offer women any incentive to have children.

The Osaka prefectural government had provided annual financial support to a number of institutions in the prefecture, some of them are the election of a new prefectural governor in the 2008 elections, the annual financial support started to be withdrawn from 2009.7

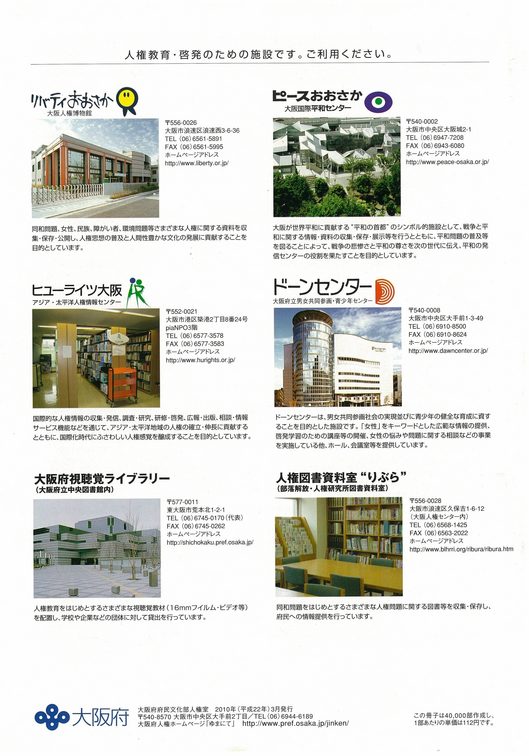

Some of the human rights institutions that had received financial support from the Osaka prefectural government. Source: Back cover of Humanite, volume 24 (2010)

Conclusion

The Osaka prefectural government could be doing more to significantly distinguish its human rights policies from those of the national government, which have been criticized on a number of issues by the United Nations human rights bodies.8 In explaining this, Osaka prefectural government officials stressed the difference in values between the West and Japan. Yet the fact remains that the Osaka government has an opportunity to be the leader in a renewed Japan’s efforts to become a more tolerant, positive international presence, one that proves to the world that all of the wonderful, unique aspects of Japanese culture are every bit as respectful of human rights as those of other countries, and in some ways perhaps even more. That does not appear to be happening, however.

Mr. Joseph Lavetsky, currently a second year student at the Emory University Law School in the U.S.A., was a 2010 summer intern in HURIGHTS OSAKA.

For further information, please contact HURIGHTS OSAKA.

Endnotes

1. The full text of this ordinance, in Japanese language, is available at www.pref.osaka.jp/jinken/measure/jyourei.html

2. See Osaka Prefecture’s Policy Regarding Foreign National Residents in www.pref.osaka.jp/ en/life/general/f_citizens.html.

3. See www.pref.osaka.jp/jinken/ (in Japanese language) for the Human Rights Office profile.

4. For more information on the Osaka prefectural government human rights policies, please visit www.pref.osaka.jp/jinken/measure/ (in Japanese).

5. The Osaka prefectural government, however, has been supporting specific human rights education initiatives for secondary schools such as those on Buraku discrimination (called Dowa education), especially during the period of the special measures law.

6. The Osaka Foundation of International Exchange website, www.ofix.or.jp/english/ofix/ index2.html.

7. See “Prefectural Policy Change and Human Rights Work: The Case of HURIGHTS OSAKA” in issue 52 of this newsletter for a report on the financial support withdrawal. The article is available at www.hurights.or.jp/ archives/focus/section2/2008/06/prefectural-policy-change-and-human-rights-workthe-case-of- hurights-osaka.html

8. Such criticisms have been mentioned, for example, in the Concluding observations of the United Nations’ Human Rights Committee, CCPR/C/JPN/CO/5, 18 December 2008, and the Concluding observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, CERD/C/JPN/CO/3-6, 6 April 2010.