- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- December 2011 - Volume Vol. 66

- Extrajudicial Killing and Enforced Disappearance in South and Southeast Asia

FOCUS December 2011 Volume Vol. 66

Extrajudicial Killing and Enforced Disappearance in South and Southeast Asia

In 1983, a group of prominent human rights personalities in Southeast Asia made a collective plea to the Association of the Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) that in addressing public emergencies the:1

Government shall not, under any circumstances, resort to or authorize:

(a) Violence to life, health and physical or mental well-being of persons who are not or are no longer combatants in armed conflict, in particular, murder, political assassination or extra legal executions, kidnapping or unexplained disappearances, torture, mutilation or any form of corporal punishment, use of so-called truth serums and other drugs, and slavery or other forms of involuntary servitude. (Article XI [4] Public Emergencies)

This statement, among others, reflected the prevailing situation in a number of countries in Southeast Asia in the 1970s and 1980s.

What were then known as political assassinations or extra legal executions and unexplained disappearances are now termed by the United Nations as extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances respectively. In the Philippines, extrajudicial killing has been known as “salvaging” since the 1970s or during the period when the country was under martial rule.

A decade later, in 1993, Asian human rights organizations appealed to the Asian governments to take “urgent and effective” action on a number of issues including “political repression by means of killings, disappearances, and torture.”2 The Asian governments’ declaration however failed to mention this matter, though the document mentioned threats due to all forms and manifestations of terrorism.3

Continuing Concern

While changes in the political situation in many countries in South and Southeast Asia occurred during the recent years, the overall situation of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances has hardly changed. Some reports illustrate the seriousness of the situation during the last decade.

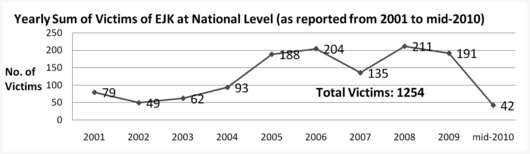

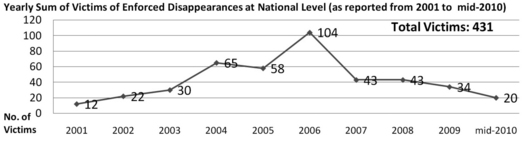

Statistics from the Philippine Commission on Human Rights covering 2001 to 2010 period,4 Graphs 1 and 2, show increased number of cases during the last five years.

Graph 1. Extrajudicial killings (Philippines)

Graph 2. Enforced Disappearances (Philippines)

In India, the Asian Center for Human Rights tallied the figures from the National Human Rights Commission of India on reported deaths in police and judicial custody and came up with the statistics in Table 1.5

Table 1. Deaths in Police & Judicial Custody (India)

| Year | Police Custody | Judicial Custody |

| 2000-2001 | 127 | --- |

| 2001-2002 | 165 | 1,140 |

| 2002-2003 | 183 | 1,157 |

| 2003-2004 | 162 | 1,300 |

| 2004-2005 | 136 | 1,357 |

| 2005-2006 | 139 | 1,591 |

| 2006-2007 | 119 | 1,477 |

| 2007-2008 | 187 | 1,789 |

| 2008-2009 | 142 | 1,527 |

|

2009-2010 (February) |

124 | 1,389 |

| 2010-2011 | 147 | --- |

| Total | 1,631 | 12,727 |

Reports from Bangladesh by ODHIKAR6 show data regarding deaths attributed to “crossfire” and torture involving members of the police, members of other enforcement agencies, and members of the security forces. Table 2 provides some data.

Table 2. "Crossfire" and "Torture to death" (Bangladesh)

| Year | Crossfire | Torture |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 166 | 46 |

| 2005 | 340 | 24 |

| 2006 | 290 | 27 |

| 2007 | 130 | 30 |

| 2008 | 136 | 12 |

| 2009 | 129 | 21 |

| 2010 | 101 | 12 |

| 2011(Jan.-Aug.) | 44 | 12 |

|

Total |

1,336 |

194 |

In Pakistan, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) noted in its 2010 report7 the continuing trend of killings and disappearances. Several hundred people died due to police encounters (with few “suspects” being captured alive), targeted killings, and deaths in prison. There are also reports of almost sixty missing persons, while the dead bodies of some reported missing persons had been found. More than thirty cases of enforced disappearances had been reported. Statistics on missing persons over a ten-year period are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. HRCP list of reported missing persons (Pakistan) (traced and still missing)8

| Year | Traced Missing Persons | Still Missing |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 3 | 2 |

| 2001 | --- | --- |

| 2002 | 3 | 1 |

| 2003 | 3 | --- |

| 2004 | 9 | 2 |

| 2005 | 33 | 4 |

| 2006 | 75 | 20 |

| 2007 | 30 | 11 |

| 2008 | --- | 2 |

| 2009 | 3 | 28 |

|

Total |

159 |

70 |

The National Human Rights Commission of Nepal reported the number of cases of extrajudicial killings and the disappearances in Table 4.

Table 4. Extrajudicial killings and disappearances9 (Nepal)

| Year | Extrajudicial killings | Disappearances |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 3 | --- |

| 2002 | --- | --- |

| 2003 | 6 | 13 |

| 2004 | 15 | |

| 2005 | 45 | 1 |

| 2006 | 38 | 1 |

| 2007 | 22 | |

| 2008 | 56 | |

| 2009 | 54 | 1 |

|

Total |

239 |

16 |

These statistics show fluctuating number of cases over the years. What could have brought the increase in the number of cases in some of those years?

In Sri Lanka, the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances has “transmitted 12,230 cases to the Government; of those, 40 cases have been clarified on the basis of information provided by the source, 6,535 cases have been clarified on the basis of information provided by the Government, and 5,653 remain outstanding.”10

Characteristics

Members of the police, security forces and paramilitary groups have long been suspected of perpetrating extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. In South Asia, extrajudicial killings have invariably been called “fake encounters” or “crossfire” killings to describe cases of people who got killed because they were allegedly members of rebel or insurgent groups and fought members of the police or security forces. A report from India, for example, indicates that the victims have actually been detained or arrested, unarmed, and unlikely members of any rebel or insurgent groups.11

In most countries in South and Southeast Asia, extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances have been linked to internal armed conflict or the anti-terrorism campaign.

As shown in the earlier tables, “deaths in custody” or deaths resulting from torture are also widely reported in South Asia. The police attribute these deaths to either natural causes or self-inflicted injury, but the involvement of suspicious circumstances suggest deaths caused by torture, ill-treatment or outright killing by officials. “Death in custody” is considered a type of unlawful killing under the mandate of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions.12

The 2011 report of the Commission of Human Rights of the Philippines refines the list of perpetrators by identifying them in Table 5.13

Table 5. Perpetrators of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances (2001 to mid-2010)

| Perpetrators | Exrajudicial killings | Enforced disappearances |

|---|---|---|

| Police | 25% | 13% |

| Military | 38% | 31% |

| Public Officials | --- | 1% |

| Other armed groups/insurgents | 37% | 6% |

| Civilians | --- | 14% |

| Unidentified | --- | 35% |

The 2010 report of the National Human Rights Commission of Nepal identified the perpetrators of extrajudicial killings as security forces, members of the Communist Party of Nepal, and others.14

The victims of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances include a variety of people including suspected members of rebel or insurgent groups, journalists, suspected criminals, members of minority groups, political activists and ordinary people. In a number of cases, human rights defenders have become victims, and also people suspected of being related to the drug trade (in the case of Thailand).

The cases of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances have been reported in places where active campaigns against terrorism or insurgency exist. This is seen in Balochistan in Pakistan,15 southern Thailand, southern Philippines and other regions of the country with communist insurgency, several regions in Indonesia (Aceh, Maluku, Papua and West Papua),16 Punjab and Manipur states in India, and places where the Maoist movement was strong in Nepal.17 But cases have also been reported along borders of countries like India and Bangladesh, and other places where criminal acts are alleged to exist (as in the anti-drugs campaign in Thailand).

Causes

National counter-insurgency and anti-terrorism policies along with the culture of impunity among state agents, weak laws, weak judicial system, and weak National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs) combine to create an environment for the perpetration of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances.

In many cases, “enemies” are identified and targeted for disappearances (2001 to mid-2010) police or military action. However, the “enemies” are not merely rebel or insurgent groups but also “leftist” organizations, trade unions and civil society organizations (including human rights organizations), and journalists.18 The situations in Manipur (India) and Balochistan (Pakistan) illustrate the problem:

• During the 2009, 1,119 cases of illegal arrest and detention were documented while one hundred forty two cases of extrajudicial killings were reported in the province of Manipur alone.19 Also, deaths in police custody are of alarming concern.

• In the same year, in the conflict-stricken province of Balochistan, more than three thousand five hundred people were extra-judicially killed and some four thousand people were reported missing.20

It seems that whenever governments launch special programs to address a national problem using the police and the security forces, a sudden rise in the number of killings that qualify as extrajudicial killings occur. This happened in Thailand during the 2003-2004 period in relation to the “war of drugs”21 and in Bangladesh in 2002 (“Operation Clean Heart”) and 2004 (with the formation of an “elite force known as Rapid Action Battalion or RAB). There can also be an increase in number of deaths due to political upheavals such as the 2010 political violence in Thailand.22

Actions Taken at the National Level

Extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances should be properly investigated in order to make those who committed the crime accountable, and to give justice to the victims. Wherever they exist, national human rights institutions should investigate and recommend the prosecution of these cases particularly when members of the police and security forces are involved. The respective national human rights institutions in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand, investigate reports of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances, and recommend the prosecution of people found to be responsible for the crimes. They also do other measures. The National Human Rights Commission of India laid out in 1997 guidelines for the state governments to effectively and properly address the issues of encounter killings and custodial deaths. The guidelines were revised in 2003.23 It also strongly stated that “the anti-terrorism and anti-militancy measures must be directed only against perpetrators or abettors of these acts and not against innocent citizens.”24 The National Human Rights Commission of Thailand has requested the Thai government to sign “but not ratify, pending changes in domestic law” the Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances.25 The Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines has been lobbying for enactment of laws on extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances.26 However, the national human rights institutions have limited powers in preventing impunity regarding extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. They have no power to enforce their recommendations. The recommendations issued by the National Human Rights Commission of Nepal “to take legal action against the human rights violators associated with the security forces and those affiliated to various political parties have not been implemented” by the Nepali government.27 This is probably true of other national human rights institutions. Thus they resort to collaborating with various institutions ( governmental, non-governmental, and international institutions) to address human rights issues.

Intense local media coverage and international pressure on extrajudicial killings in 2006 forced the Philippine government to create a commission (known as the Melo Commission) that investigated cases of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances and gave recommendations on how to address the problems, a special monitoring body of the police (the Philippine National Police’s Task Force Usig), a special investigative body (the Task Force against Political Violence) on political violence, and another commission (the Independent Commission to Address Media and Activist Killings) that investigated media and political killings and gave policy recommendations. Similar special bodies have been established in Sri Lanka28 (special units under theDepartment of the Attorney General to address the extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances as well as other human rights violations such as the Missing Persons Unit and the Habeas Corpus Unit),29 and in Pakistan (Commission of Enquiry on Missing Persons).

The Philippine Supreme Court organized a national conference in 2007 to discuss measures to stop extrajudicial killings. It also adopted the Rule on the Writ of Amparo, effective since 2007, to provide a remedy in extrajudicial killing and enforced disappearance cases.30

In the legislative branch, bills have been filed to criminalize extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances in the Philippines.31 The Bangladeshi Parliament took several positive initiatives in 2009 to enact laws that promote and protect human rights, including the National Human Rights Commission Act 2009 and the Code of Criminal Procedure Act 2009.32 But in the same year it also passed the Anti-Terrorism Law in its first session without consultation with the general public, as reported by ODHKAR.33

The Pakistani media reported the recent decision of the Ministry of Human Rights of Pakistan to create a task force that would probe human rights violations in Balochistan. This body is being formed in the context of the "surfacing of thousands of deaths and abduction cases in Balochistan, where political workers and students are routinely found missing and then dead."34 The media also pointed out the need to look into the military operation in the province, as well as the “kill and dump” policy being pursued by the military and its intelligence agencies.35

Final remarks

As clearly seen, extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances are widespread in many Asian countries due to both political and non-political reasons. Despite varying national contexts and factors, extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances were most likely perpetrated by state agents under the pretext of national security in an attempt to eliminate real and perceived enemies, and intimidate oppositionists and the general public.

Such systematic human rights violations can only be deterred by the political will of governments in taking resolute action against them at all levels.

Munty Khon was an intern in HURIGHTS OSAKA during the summer of 2011 under the Asia Leaders Programme (masteral course) of the University for Peace.

For further information, please contact HURIGHTS OSAKA.

Endnotes

1. This is article 4 of the Declaration of the Basic Duties of ASEAN Peoples and Governments. See full text of the declaration in HURIGHTS OSAKA website: www.hurights.or.jp/archives/other _document s /section1/1983/03/declaration- of-the-basic-duties-of-asean-peoples-and-governments.html.

2. This is taken from Bangkok Declaration on Human Rights, the non-governmental organization statement to the Regional Meeting for Asia of the World Conference on Human Rights, March 1993.

3. “Final Declaration of the Regional Meeting for Asia of the World Conference on Human Rights.” See A/CONF.157/ASRM/8 A/CONF.157/PC/59, 7 April 1993. Full text of the document available at www.unhchr.ch/Huridocda/ Huridoca.nsf/TestFrame/9d23b88f115fb827802569030037ed44?Opendocument.

4. Graphs taken from powerpoint presentation entitled “Philippine Trends on Human Rights Violations” prepared by the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines, July 2011.

5. See report of the Asian Centre for Human Rights, Torture in India 2010, page 2, and the 2011 report, Torture in India 2011, pages 2 and 3.

6. Data drawn from the separate statistical tables “crossfire” and “torture to death” respectively available at ODHIKAR’s website: www.odhikar.org/stat.html.

7. See report of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, State of Human Rights in 2010, pages 6 and 7.

8. Data drawn from Human Rights Commission of Pakistan documents on “Missing Persons” available at www.hrcp-web.org/default.asp.

9. Data drawn from Summary Report of National Human Rights Commission Nepal (2000-2010), November 2010, page 3.

10. See Report of the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances 2010, A/HRC/16/48, page 99.

11. See Human Rights Initiative, Human Rights Special ReportManipur 2009 (India: Human Rights Initiative Publication, 2009).

12. See Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary killings, Philip Alston, A/HRC/14/24, 20 May 2010, page 12.

13. Supra note 4.

14. See report of the National Human Rights Commission of Nepal, Summary Report of National Human Rights Commission Nepal (2000-2010), pages 8 and 12.

15. See for example, Human Rights Watch, We Can Torture, Kill, or Keep You for Years: Enforced Disappearances by Pakistan Security Forces in Balochistan, Retrieved 10 September 2011 from www.hrw.org/reports/ 2011/07/25/we-can-torture-kill-or-keep-you-years.

16. KONTRAS, Enforced Disappearances, Summary and Extrajudicial Killings Inside Indonesia’s Counter Terrorism Laws, Policies and Practices. Retrieved 09 September 2011 from ejp.icj.org/IMG/KONTRASSubmission.pdf.

17. See Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions: Mission to Nepal, E/CN.4/2001/9/Add.2.

18. See Maria Socorro I. Diokno, Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions in the Philippines, 2001-2006 (unpublished), pages 2-3, 8. An edited version of this document was published in FOCUS Asia- Pacific, 48/2007, and available at www.hurights.or.jp/archives/focus/section2/2007/06/extrajudicial-summary-or- arbitrary-executionsin-the-philippines-2001-2006.html.

19. Supra note 11.Z

20. Asian Human Rights Commission, The State of Human Rights in Ten Asian Nations 2009 (Hong Kong: Asian Human Rights Commission Publication, 2009).

21. See Pasuk Phongpaichit and Chris Baker, “Slaughter in the Name of a Drug War,” New York Times, 24 May 2003.

22. See Justice for Peace Foundation, “Report on the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand 2010,” in 2011 ANNI Report on the Performance and Establishment of National Human Rights Institutions in Asia (Bangkok: FORUM-ASIA, 2011), page 268.

23. The guidelines can be downloaded at www.nhrc.nic.in/. The guidelines set out procedures on reporting, investigation, prosecution and compensation in all cases of encounter deaths and custodial deaths.

24. See National Human rights Commission of India, Annual Report 2007-2008, page 23.

25. Supra note 22, page 280.

26. The Lawyers League for Liberty, “Philippines: A Time of Vigilance and Hope,” in 2011 ANNI Report on the Performance and Establishment of National Human Rights Institutions in Asia (Bangkok: FORUM-ASIA, 2011), pages 216-217.

27. Supra note 14, page 20.

28. Sri Lanka in the past has also had several human rights bodies. These bodies include the Ombudsman with the mandate to investigate cases of human rights violations; Human Rights Centre of the Sri Lanka Foundation to address the issue of discrimination; Commission for the Elimination of Discrimination and Monitoring of Fundamental Rights to provide conciliation services; Human Rights Task Force to investigate and monitor cases of custodial detention and disappearances; and a number of ad hoc commissions to deal with specific issues, including disappearances. For details, see HURI GHTS OSAKA, “Government Human Rights Work: National Human Rights Institutions,” in Jefferson R. Plantilla & Sebasti L. Raj, SJ (editors), Human Rights in Asian Cultures – Continuity and Change (New Delhi: HURIGHTS OSAKA, 1997).

29. See the National Report by the Government of Sri Lanka submitted to the Human Rights Council for the Universal Periodic Review, A/HRC/WG.6/4/BGD/1, (19 November 2008).

30. See Adolfo S. Azcuna, The Philippine Writ of Amparo: A New Remedy for Human Rights. Retrieved 09 September 2011 from www.venice.coe.int/WCCJ /Papers/PHI_Azcuna_E.pdf.

31. See Vincent Michael Borneo, Does the Philippines need an anti-EJK law?, Retrieved 09 September 2011 from www.targetejk.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=66: does-the-philippines-need-an-anti-ejk-law&catid=7:extra-judicial-killings&Itemid=14.

32. For details see Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), Human Rights in Bangladesh 2009: A Summary Report, available at http://www.askbd.org/web/?page_id=430.

33. See ODHIKAR, Human Rights Report 2010 on Bangladesh, available at http:// www.odhikar.org

34. “Balochistan violence: Human rights ministry to form task force,“ The Express Tribune, 21 November 2011, http://tribune.com.pk/story/294761/rising-violence-in-balochistan-human-rights-ministry-to-form-task-force/

35. “EDITORIAL: Baloch blood on our hands,” The Daily Times, 21November 2011, www.dailytimes.com.pk/default.asp?page=2011\11\21\story_21-11-2011_pg3_1