- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- June 2013 - Volume Vol. 72

- Facts and Figures: Violence Against Religious Minorities

FOCUS June 2013 Volume Vol. 72

Facts and Figures: Violence Against Religious Minorities

Violence against religious minorities continues in several countries in Asia. The violence against the Rohingyas in Burma/Myanmar in recent months exemplifies the complexity of the situation that brings out this kind of violence against particular groups of people.

In recent years, documentation of violence against religious minorities reveals the variety of violent actions being perpetrated, the different communities involved, and the people who use violence against them. This documentation is indispensable

in finding ways to minimize (if not stop) the violence against religious minorities.

Indonesia

The SETARA Institute has been documenting cases of violence related to the violation of the right to freedom of religion and belief in Indonesia since 2007. It has been issuing annual reports on the situation in many provinces of Indonesia regarding freedom of religion and belief.

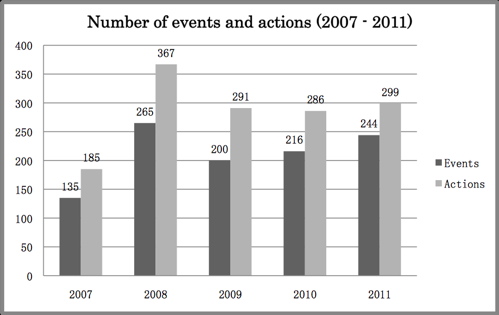

The 2010-2012 data gathered by the Setara Institute show that violations of the right to freedom of religion and belief have occurred in many provinces in Indonesia. See Table 1 for the list of provinces with considerable number of cases recorded.1 Data for the 2007-2011 period show a generally high number of “events and actions” that led to violation of the right to freedom of religion and belief, see Table 2.2

Table 1. Provinces with considerable number of cases of violation

| Province | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

| North Sumatra | 15 | 24 | 3 |

| West Sumatra | 5 | 7 | 2 |

| North Sulawesi | 1 | 24 | 2 |

| South Sulawesi | 9 | 45 | 17 |

| Riau | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Papua | 1 | 3 | |

| East Nusa Tenggara | —— | 2 | 1 |

| West Nusa Tenggara | 7 | 12 | 4 |

| Lampung | 8 | 5 | 1 |

| East Kalimantan | —— | 5 | 2 |

| South Kalimantan | —— | —— | 12 |

| East Java | 28 | 31 | 42 |

| Central Java | 10 | 11 | 30 |

| West Java | 91 | 57 | 76 |

| DKI Jakarta | 16 | 9 | 10 |

| D.I. Yogyakarta | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Bengkulu | —— | —— | 2 |

| Banten | 6 | 12 | 4 |

| Bali | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Aceh | —— | 8 | 3 |

Table 2. Events and Actions during the 2007-2011 period

The 2010-2012 data show that most violations of the right to freedom of religion and belief occur in West Java province. Table 3 shows the consistent high number of violations over a three-year period in that province. East Java follows with the second highest number of cases of violations.3

Table 3. Provinces with the highest number of cases of violation

| Province | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

| West Java | 91 | 57 | 76 |

| East Java | 28 | 31 | 42 |

| Central Java | 10 | 11 | 30 |

| Sulawesi Selatan | 9 | 45 | 17 |

| Aceh | — | 8 | 36 |

The Setara Institute notes that West Java is the most densely populated province in the country, and thus assumed to have the highest level of diversity in a variety of ways including religious belief. The high rate of violations of right to freedom of religion and belief in West Java shows high level of intolerance.4

The acts of violence that violate the right to freedom of religion and belief have been directed at different communities including those of the Buddhists, Ahmadiyyas, and Christians.

Among the affected communities, those with the highest number of victims belong to the Christian and Ahmadiyya groups, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Victims of violations of right to freedom of religion and belief

| Group | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

| Christian | 75 | 54 | 50 |

| Ahmadiyya | 50 | 114 | 31 |

| Shia | —— | 10 | |

| Religious sects | ——- | 38 | 42 |

| Buddhist | 9 | 2 | 7 |

There are many other groups that have suffered violations along with a significant number of individual victims.

The Setara Institute has classified the violators into state and non-state actors. For the 2010-2012 period, non-state actors have been involved in most of the incidents that violate the right to freedom of religion and belief. The cases involve religious organizations and individuals, and other non-state organizations. The violent acts committed consisted of killings, acts of torture, sporadic physical attacks, and destruction of places of worship, residences and other properties. They have also threatened the victims with the violent attacks, disallowed religious activities, and did other discriminatory and intolerant acts.

State actors (members of the police, and officials of national and local government agencies) have been involved in violating the right to freedom of religion and belief. The members of the police have the highest number of reported violations. The 2012 report lists the direct acts committed by state actors including the prohibition of establishment of places of worship, forcing beliefs on people, dispersing groups discussing religious matters, stopping religious activities, investigation of allegations of religious desecrations, and prosecution of allegations of religious desecration cases.5

Pakistan

The Jinnah Institute, a Pakistani non-governmental think tank, advocacy group and public outreach organization, has been researching on the status of religious minorities in Pakistan. As stated in its 2011 report (A Question of Faith: A Report on the Status of Religious Minorities in Pakistan), the “most recent attacks on religious minorities and the state's tolerance towards this persecution are part of a longer-term pattern of state complicity at all levels - judicial, executive and legislative - in the persecution of and discrimination against minorities.”6

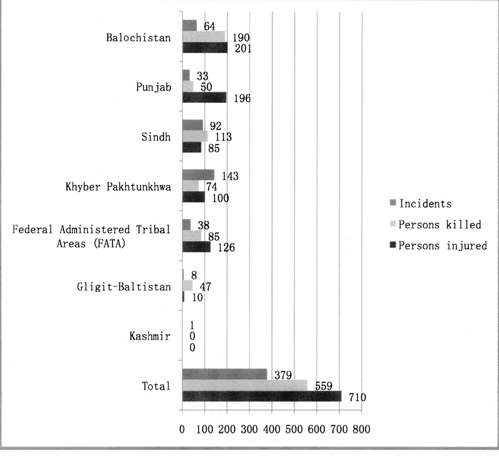

During the November 2011 - December 2012 period, incidents of attack against minorities have occurred in several provinces in Pakistan, namely, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, Balochistan, Federal Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), and Punjab. There were three hundred seventy-nine incidents with five hundred fifty-nine people getting killed and seven hundred eighteen people getting injured.7 See Table 5 for the breakdown of the figures.

Table 5. Incidents by Province - November 2011-December 2012

Members of Shia, Ahmadiyya and Sufi communities along with Christian, Hindu, Sikh and other communities have been killed, maimed and displaced by various forms of extremist actions. The 2012 report, Extremism Watch – Mapping Conflict Trends in Pakistan 2011-2012, defines the forms of extremisms experienced in Pakistan:8

a. Interfaith extremism – incidents of incendiary speech or writing; physical attacks directed against (or exchanged between) members of different faiths, their property, religious symbols, congregations and places of worship. Incidents involving Muslim, Christian, Hindu, Sikh, and other communities have been recorded under this category. Blasphemy related incidents form a subset of interfaith extremism.

b. Sectarian extremism – incidents of incendiary speech or writing; physical attacks directed against (or exchanged between) members of different Islamic sects, their property, religious symbols, congregations and places of worship. Incidents recorded under this category mostly include suicide attacks on Shia religious processions and target killings. To a lesser degree, attacks against the Bevi mosques and funerals, as well as clashes between Barelvi and Ahl-e-Hadith groups have been recorded.

c. Shrine attacks – attacks on Sufi shrines, congregations and devotees. Although attacks against shrines may constitute a subset of sectarian violence, they are presented separately as they form a relatively new and distinct kind of religious extremism.

d. School attacks – physical attacks against private and public school infrastructure, violence, intimidation or harassment of students, teachers and parents.

e. Other forms of religious extremism include bombing of “CD shops,” wall chalking and other defacement; non- violent forms of religious extremism.

Many of the incidents are attributed to radical religious groups, and some are linked to the Taliban and Al Qaeda networks.9 The rise of religious extremist groups parallels the weakening of state institutions in stemming the violence from these groups.10 Investigation of the incidents have been found wanting leading to failure to prosecute perpetrators in court and no clear national policy has been discussed to address the serious problem of violence against religious minorities. There has also been an absence of public dialogue on the root causes of the violence against religious minorities, and how to stop the violence.

Final Note

The documentation undertaken by the Setara Institute in Indonesia and the Jinnah Institute in Pakistan helps clarify the issue of violence against religious minorities from a broader perspective. Their analysis of the respective situations in Indonesia and Pakistan points to the need for political will on the part of the government to resolve the issue in ways that address the root causes of the violence and through means that strengthen the role of the affected communities in the conflict

resolution process.

For further information, please contact HURIGHTS OSAKA.

Endnotes

1. The figures in Table 1 were drawn from the following reports of Setara Institute: Denial by the State - Report on Freedom of Religion and Belief in 2010; Political Discrimination – The Condition of Freedom of Religion and Belief in 2011; and Leadership Without Initiative – The Condition of Freedom of Religionand Belief in 2012. These reports are available at www.setara-institute.org/en/category/category/reports/religious-freedom.

2. See Denial by the State - Report on Freedom of Religion and Belief in 2010, available at www.setara-institute.org/en/content/report-freedom-religion-and-belief-2010-0.

3. The figures in Table 3 were likewise drawn from the 2010, 2011 and 2012 reports of Setara Institute listed in note 1.

4. See Bonar Tigor Naipopos, editor, Leadership Without Initiative – The Condition of Freedom of Religion and Belief in 2012 (Jakarta: Setara Institute, 2013), page 31.

5. Ibid., pages 36-38.

6. A Question of Faith: A Report on the Status of Religious Minorities in Pakistan (Jinnah Institute, 2011) page 5. Full document available at www.jinnah-institute.org/ji-fos/306-a-question-of-faith-a-report-on-the-status-of-religious-minorities-in-pakistan

7. Extremism Watch – Mapping Conflict Trends in Pakistan 2011-2012 (Jinnah Institute, 2011) page 7. Full document available at www.jinnah- institute.org/extremism-watch-mapping-conflict-trends-in- pakistan-2011-2012.

8. Ibid., page 6.

9. Syed Baqir Sajjad, ““Intent to Destroy”: Violence Against the Shias in Pakistan,” in Extremism Watch – Mapping Conflict Trends in Pakistan 2011-2012, ibid., page 19.

10. See Ayesha Siddiqa, “The Radicalism-Extremism Nexus,” in Extremism Watch – Mapping Conflict Trends in Pakistan 2011-2012, ibid., pages 14-18.