The Minister for Justice said the Fijian Parliament had approved a bill to remove all references to the death penalty in military laws, and therefore abolishing the dea[th] penalty from all national legislation. Fiji was aware that there were patriarchal notions of power relations as well as challenges in tackling violence against women at the legislative and community levels. However, huge progress had been made in establishing a legislative framework for addressing violence against women, including new legal provisions for the offences of rape and sexual assault based on the Australian model as well as domestic violence and child abuse. Fiji encouraged civil society to undergo legal training on the effective implementation of the laws, which were designed to remove discrimination and violence against women.

Two member-states expressed concern about restrictions on freedom of expression under the Constitution, while one member-state noted the restrictions in the Media Decree and the impact of the Public Order Amendment Decree on the exercise of freedom of peaceful assembly. Part of the government response to the issue is as follows:

While guaranteeing freedom of speech, expression, thought, opinion and of the press, the Constitution explicitly prohibited any speech, opinion or expression that was tantamount to war propaganda, incitement to violence or insurrection against the Constitution, or advocated hatred based on any of the prohibited grounds of discrimination, which included race, culture, ethnic or social origin, sex, gender, sexual orientation and gender identity, language, economic, social or health status, disability, age and religion. Those limitations were also in line with general recommendation No. 35 of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination on combating racist hate speech.

The Fijian government officials also reported on new initiatives related to human rights including updated provisions in the Crimes Decree for the offences of rape and sexual assault, the implementation of the Domestic Violence Decree, judicial training, a new National Gender Policy and gender training for civil servants.

During the 2015 UPR session, the government delegation of Kiribati reported on the implementation of the “National Approach to Eliminating Sexual and Gender Based Violence: Policy and Strategic Action Plan” and the existence of “SafeNet, a committee that comprised government ministries, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and faith-based organizations providing front-line services to victims of domestic violence ... in most islands of Kiribati.” The Children, Young People and Family Welfare Policy, aimed at protecting children against abuse, violence, neglect and exploitation, was adopted. Kiribati criminalized domestic violence through the Family Peace Act 2014 (Te Rau N Te Mweenga Act) and established the Ministry of Women, Youth and Social Affairs. The Kiribati Constitution was amended to prohibit discrimination based on race, colour and national origin.

The government delegation of Kiribati highlighted climate change as the major challenge faced by the country. The delegation explained that as

a nation of low-lying islands, with an average elevation of only 2 metres above sea level, climate change and the resultant sea-level rise had added new and major challenges for Kiribati, including loss of territory, severe coastal erosion and involuntary displacement of communities, affecting food and water security. More importantly, it had become an issue of survival for the people of Kiribati.

Aside from the frequent mention of sexual and gender-based violence by member-states during the interactive dialogue of the UPR, other issues raised included the reintroduction of the death penalty, protection of the rights of persons with disabilities, the strengthening of the Kiribati National Human Rights Task Force (established in 2014), and the broadening of grounds for prohibiting discrimination in the Constitution.

The Marshall Islands report to the Human Rights Council in 2015 discussed the Domestic Violence Prevention and Protection Act 2011 and the creation of Domestic Violence Prevention and Protection Task Force in 2012 as an “attachment to the Secretary of Internal Affairs, to ensure the law was implemented, make recommendations, pool resources and lobby for the Nitijela [parliament] to provide financial support from the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ recurrent budget.”

The Marshall Islands government delegation also mentioned the “work on strengthening existing mechanism within government, including the Gender and Development Office and the Child Rights Office within Ministry of Internal Affairs;” but the government was not considering the establishment of a national human rights institution.

The government delegation cited the problem regarding the impact on human rights of the Nuclear Testing Program conducted in the Marshall Islands by the United States from 1946 to 1958. It mentioned the failure of the UN Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes to fully access in 2012 the pertinent records in the United States. Many of the historical documents provided to the Marshall Islands were incomplete

and in “deleted version only” form and labelled as “extracted, redacted or sanitized” with information of an unknown nature and the volume removed.

The government delegation also explained the challenges being faced by saying that the government “was still distributing drinking water [in some islands]… [and if] it had to decide whether to build a prison for women or a maternity ward, it would choose the latter.” The delegation also emphasized that Marshall Islands had been “subjected to forces beyond their control in terms of displacement of population as well as difficulty in providing basic health and education to their populations,” and therefore recognized the right to exist as primarily important.

The Federated States of Micronesia is a federation comprised of four autonomous States: Chuuk, Kosrae, Pohnpei and Yap. The country consists of widely dispersed islands that presented a unique challenge to governance and service delivery.

The government delegation of Micronesia explained that as a small island country it was difficult to talk about human rights without touching on the link between the adverse impacts of climate change and the right to develop, live and exist as a nation.

Micronesia enacted the Trafficking in Persons Act 2012, and the corresponding laws against trafficking in persons were enacted in all four autonomous states in 2013. It adopted the National Strategic Development Plan (2004-2023), which covered gender equality issues and steps to address them. Kosrae State enacted its Family Protection Act in 2014, the first law to criminalize domestic violence in Micronesia; while Chuuk State enacted a law that raised the age of sexual consent from 13 to 18 years.

During the interactive dialogue, several member-states cited the high number of domestic violence and trafficking cases. One member-state noted that domestic violence and the abuse of children within the family remained largely unreported as a result of social, cultural and institutional barriers.

The government delegation of Nauru explained in the 2015 report to the Human Rights Council the situation of asylum seekers in the country:

9. The Government of Nauru confirmed that, since 5 October 2015, the country’s Regional Processing Centre, which houses asylum seekers, was officially open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. This effectively meant that detention had ended and all asylum seekers were now free to move around the island at their own free will. That measure had been planned for a while after already implementing a daytime open centre programme, and had been waiting for confirmation of assistance from Australia in the transition. The new arrangements were simply an expansion of the existing open centre programme, which had been in effect for 12 hours per day. It is significant to note that the Government of Australia would be supporting Nauru with safety, security and law enforcement, including providing more Australian Federal Police assistance in that regard.

Nauru enacted several laws (Cyber Crime Act, the Adoption Act and the Education Act amendment, Child Protection and Welfare Act 2016, Crimes Act 2016), and formulated national policies on several issues (National Youth Policy 2009-2015, the National Policy on Disability 2015, the National Policy on Women 2014- 2019 and the National Sustainable Development Plan 2005-2025).

10 It also established the Gender Violence and Child Protection Directorate.

During the interactive dialogue, several member-states raised concerns about abuses suffered by asylum seekers, particularly the reports on abuses of unaccompanied refugee children/minors “who were released into the Nauruan community.”

Several member-states also expressed concern about the high rate of domestic violence in Nauru and the few cases brought to court against the perpetrators of domestic violence; and the discrimination against women.

The government officials of Palau stressed that “[L]ike other small island developing States, it depends on those [ocean and marine] resources and their protection is inextricably linked to its ability to protect and promote human rights.”

It reported on the domestic violence issue by discussing the enactment of the Family Protection Act in 2012 (which criminalized marital rape and decriminalized homosexuality), revised the Penal Code in 2014 (which included regulations on the use of force against children and other persons under the care or control of another, labor trafficking, anti-smuggling and anti-trafficking crimes and offences, as well as child exploitation, sexual assault of children and registration of sex offenders).

The government established the Family Protection Committee (to promote awareness of the new law, afford people comfort and safety in reporting sexual assault and domestic violence), gender and disability office within the Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs; hired a Human Rights Officer under the Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs, and developed policies for persons with disabilities. It also had the “no-drop policy” to ensure that although there might be reconciliation under customary practice, cases would still move forward to prosecute the perpetrators.

Several member-states cited the abuse of foreigners in Palau, including the “reported increased vulnerability to involuntary servitude and debt bondage as a result of strict labour regulations,” human trafficking, protection of children, and prison conditions.

The government of Samoa reported the enactment of several legislations in 2013 including the Family Safety Act 2013 (which provided greater protection for families and the handling of domestic violence and related matters through the use of protection orders), Crimes Act 2013 (which introduced several significant changes to provisions relating to sexual offences, such as an increase in maximum penalties; a more inclusive definition of offences, including a variety of forms of unwanted sexual contact; and the criminalization of marital rape); Labour and Employment Relations Act 2013 (which had introduced significant changes into the employment laws of Samoa, such as new maternity and paternity leave entitlements, and the introduction of new fundamental employment rights, including a ban on forced labour and equal pay for equal work), Ombudsman Act 2013 which expanded the functions of the existing Ombudsman to cover that of a national human rights institution. The Education Act 2007 prohibited corporal punishment in schools.

A 2013 constitutional amendment introduced a 10 per cent quota for women representatives in the national Legislative Assembly that led to more women being elected to the legislative body in the 2016 elections and the appointment of Fiame Naomi Mata'afa to the position of Deputy Prime Minister (and concurrently Minister of Natural Resources and Environment).

13 The Family Court of Samoa was established in 2014, while the Drugs and Alcohol Court, which was presided over by female Supreme Court judges, was established in 2015.

Most of the comments raised by member-states during the interactive dialogue recognized these changes in the laws and institutions in Samoa.

The government delegation of Solomon Islands reported that the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had been completed. This was one of the measures to address the ending of the “civil unrest between 1998 and 2003, which affected the rule of law, service delivery, development and economic activities, to name a few areas affecting basic human rights.” The delegation cited progress in combating violence against women, especially the adoption of the Family Protection Act of 2014, which criminalized domestic violence in all of its forms and sought to protect victims. The Immigration Act in 2012 and the Immigration Regulations in 2013 criminalized people smuggling and the trafficking of human beings.

The delegation mentioned the plan to expand the powers of the Ombudsman to cover human rights. A July 2017 media report stated the enactment of the bill on the Ombudsman which included the following objective: "To safeguard the rights of individuals against maladministration, abuse of power or violations of fundamental human rights by the public authorities subject to his jurisdiction."

15

The delegation also discussed measures to strengthen the judicial system, ensure inclusive education for all children, and facilitate access to water supply, housing and health services. It also reported that a number of bills on children and other issues have been prepared.

Many member-states commended the passing of the Family Protection Act in 2014 and the steps being taken to implement the provisions on sexual abuse and domestic violence. But Fiji noted the barriers to its effective implementation due to traditional attitudes in the Police Force and the judiciary, which sometimes encouraged reconciliation under pressure without putting in place measures to protect against further violence.

The government of Tonga took a clear stand on death penalty in its 2013 report to the Human Rights Council. It explained:

14. Tonga will continue to retain the death penalty as the ultimate criminal sanction under its criminal justice system for the crimes of murder and treason. The Tongan Courts have already set the guiding policy that the death penalty will only be used, in the context of murder, “in the rarest of rare cases when the alternative option is unquestionably foreclosed”. The death penalty is seen as a deterrent, and so far this has not increased the murder rate, nor is the murder rate high in comparison to the population. Tonga understands that it may be seen as a de facto abolitionist of the death penalty, however in reality it reserves its position on utilisation of the death penalty only to be used in the “rarest of rare cases,” where violence has been at its most abhorrent, the victim at its most vulnerable, the impact universally and emotionally devastating and the alternative sentences do not qualify as appropriate or acceptable alternatives.

Many member-states commented on several issues affecting human rights in Tonga such as domestic violence, discrimination against women, provisions that criminalize consensual same-sex conduct, but they also commended Tonga for democratic reforms, police training on human rights, and educational reforms.

Tuvalu

The government of Tuvalu used its “Universal Periodic Review (UPR) commitments, treaty body recommendations and [its] own internal priorities as stipulated in [its] national development plan, the Te Kakeega III" in developing “The Tuvalu Human Rights National Action Plan 2016 – 2020.”

17

The National Action Plan identifies the human rights issues in the country ranging from those arising from climate change, access to justice, health, education, infrastructure, use of force and police procedures, violence, and other issues. There are also provisions specific to children, women and persons with disabilities.

The National Action Plan includes the implementation of relevant laws including the Family Protection and Domestic Violence Act 2014, development of school curriculum to include human rights, the development of training program on human rights for the police, and other measures.

The government delegation of Vanuatu reported in 2014 to the Human Rights Council on the developments in the human rights situation in the country by citing the adoption of a number of national policies on specific issues (including the National Plan of Action for Women 2012–2016, Education for All 2001–2015, and National Strategic Plan for HIV and STIs 2014–2018, National Disability Policy and Plan of Action and the National Children’s Policy 2008–2015, Universal Primary Education Policy). The delegation spoke of the

establishment of an interim National Human Rights Committee in Vanuatu (created by Cabinet in June 2014), and the enforcement of the Family Protection Act of 2008 including the adoption of “no drop” policy by the Public Prosecutor’s Office to ensure that cases of sexual and domestic violence could not be withdrawn. The law made legal aid available to domestic violence victims.

Several member-states raised the persistent problems of domestic violence and unequal treatment of women.

Major Concerns

Ratification of Human Rights Instruments

As of August 2017,

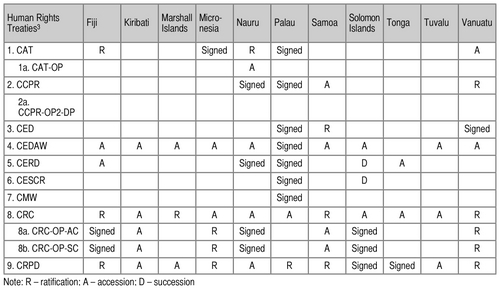

19 two Pacific small island states (Palau and Tonga) have ratified only two of the nine major human rights instruments, while two states (Marshall Islands and Tuvalu) ratified or acceded to three instruments. Only the Convention on the Rights of the Child has been ratified or acceded to by all of them; followed by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) by nine states (see Table 1). A number of UN member-states repeatedly raised during the interactive dialogue of the UPR the need to accede to all the major human rights instruments. Three states acceded to two human rights agreements after their respective UPRs; Fiji acceded to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) in March 2016, while Micronesia and Samoa both acceded to CRPD in December 2016.

The government of Tonga expressed its caution in ratifying the major human rights agreements explaining that “the introduction of new human rights would involve a delicate balancing exercise of important factors, including limited resources, core Tongan cultural values, fundamental Christian beliefs and liberal ideologies.” It saw these aspects as constituting unique circumstances in Tonga that should be recognized as reasons for the slow ratification of the core human rights conventions. The government of Tonga explained the non-ratification of CAT “because torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment were already prohibited under Tonga's criminal law, and addressed in legislation regarding evidence, extradition and mutual assistance in criminal matters.”

On the other hand, Samoa explained that it was

not procrastinating on the ratification of international treaties; it would examine all human rights conventions for possible ratification, but it would first make sure that an adequate legal framework for their implementation was in place. That exercise, which was absolutely essential, would take time.

The stance of the governments of Tonga and Samoa cannot be seen as mere excuse for slow ratification of human rights instruments, it requires serious study both by the United Nations and its member-states.

Domestic Violence

The issue of domestic violence has been raised during the interactive dialogue of the UPR on the reports of several Pacific Small Island States. A number of the states reported on the enactment of laws, adoption of policies and establishment of government mechanisms to address domestic violence. And yet the number of reported cases of domestic violence, relating to the situation of women and children, seems to remain high.

Environmental Concerns

The rising level of sea water that affects several Pacific states presents a unique issue to the region. This situation has led several affected states (Kiribati, Marshall Islands, and Micronesia) to raise it as a matter of “survival for the people” and to emphasize their “right to exist as primarily important.” Other environmental concerns, being attributed to climate change, are equally emphasized as major problems that would prevent the full realization of human rights.

Culture and Human Rights

The government officials of Marshall Islands explained the matriarchal society in Marshall Islands and the related problems with the current situation in society:

Traditionally, women dealt with the most important aspect of island life, the passage of land rights. The sense of belonging to the community in an extended family or a clan situation was based on where you must work, own land and be a caretaker for the future children of that land. That aspect, which was the most important [part] of Marshallese society, influenced the behaviour of adults in the community. Over the past decades, with the urbanization of the island population, with the need to be displaced not just by choice but for various reasons including drugs, famine, floods and other reasons, the population had not lent itself to the traditional manner of dealing with extended family issues. As a result, it had to rely on modern law and processes to which access was limited and of which it had an even more limited understanding.

The interaction between “modern law and processes” and socio-cultural values and traditions is an important issue that should be dealt with by many of the Pacific Small Island States.

Nuclear Testing

Marshall Islands raised the unresolved issue of effects of nuclear testing by the United States in its territory from 1946 to 1958. To the Marshall Islands government, the refusal or failure of the United States to provide full access to those records could only be taken as a “blatant indignity towards and lack of respect for the Marshallese people and represented an ongoing violation of basic human rights.”

Processing of Asylum Applications

Nauru reported that it has allowed the asylum seekers in its territory more freedom and the opportunity to be integrated into the Nauran society. However, several member-states remain critical of the system adopted for processing asylum applications for Australia through another country.

For more information, please contact HURIGHTS OSAKA.

Endnotes