- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- December 2017 - Volume 90

- Filipinos in Kansai: Living Within Japanese Society

FOCUS December 2017 Volume 90

Filipinos in Kansai: Living Within Japanese Society

Filipinos constitute the third largest group of foreigners in Japan with almost 250,000 population.1 23,000 of them reside in the seven prefectures of the Kansai region.2

Arrival in Kansai

From early 1920s till early 1940s, Filipino jazz musicians were playing in Kobe and Osaka. Filipino male musicians played in many entertainment places around US military bases in Japan from the 1950s, but in Kansai they started to arrive in bigger number from the 1970s to the 1980s. At the end of World War II, a number of Filipino women married to Japanese men arrived in Kansai from the Philippines (via Nagasaki) with their children. From the 1980s to mid-2000s, Filipino women as overseas contract workers (popularly known as entertainers) arrived in big number. Many of them became spouses of Japanese and started residing in Kansai to raise families.

Supported by the booming economy during the “bubble era” and the revision of Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act that took effect in 1990, many Japanese-descent Filipinos along with Filipino technical intern trainees came to Japan to supply labor to the industries in increasing number in the 1990s. Nurses and caregivers started to arrive in Kansai under the Japan-Philippine Economic Partnership Agreement (JPEPA) from 2009. Almost at the same time, Japanese-Filipino children came to reside in Japan along with their Filipino mothers, some of whom were recruited to work in hospitals and caregiving institutions (such as facilities for the elderly). And from 2017, young Filipinos aiming to work in the caregiving industry in Kansai started to arrive to study Japanese language and prepare for caregiving licensure examinations. A few Filipinos arrived in Kansai in 2017 for training on domestic help work before deployment by companies to Japanese households.

On the other hand, since 1980s, Filipinos have been arriving and residing in Kansai as spouses, professionals working in various fields, religious missionaries, and students. There are Filipinos working in international schools in Hyogo and Osaka prefectures; some teach in Japanese public and private universities in Kansai; others teach in English language schools and as Assistant Language Teachers in primary and secondary schools. Some Filipinos who studied in Kansai eventually joined the academe or worked in companies. Filipino religious missionaries (priests, nuns, pastors) work in Catholic and Christian churches in many cities in Kansai; other professionals (engineers or those engaged in technical jobs) come to Kansai for intracompany assignments or for training.

The arrival of Filipinos in Kansai continues due to a variety of reasons – family, education and new employment opportunities.

Living in Japanese Society

Filipinos do not reside as one community in one place in Kansai; they reside in the different cities and towns of the region. Among the permanent and long-term Filipino residents, many are spouses, parents and in-laws in Japanese (-Filipino) families. There are also Filipino families living in Kansai, many of whom are Japanese-descent Filipinos.

Japanese-Filipino children born in Japan from late 1980s and early 1990s have grown up and joined the workforce; some have families and children of their own.

Issues

Foreigners in Japan generally suffer from problems regarding the family, school, workplace, and relationships with fellow foreigners and the Japanese.

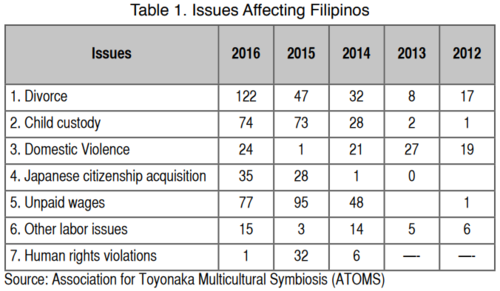

The Association for Toyonaka Multicultural Symbiosis (ATOMS), which has been providing services to foreign residents in Toyonaka and other cities for the past several decades, lists the major problems sought for consultation by Filipinos in Table 1:3

SINAPIS (Social Action Center of the Catholic Archdiocese of Osaka) recorded similar problems of foreigners in general: residence status, welfare assistance, child-support allowance, application for Japanese nationality, unpaid wages, school/ education problems, legal support and domestic violence.4

In general, the number of domestic violence cases in Japan rose when the economy was not in good condition;5 and poverty rate among single parent families reached 55 percent in recent years.6

Family-related and economic problems (such as irregular income or unstable employment of the Japanese spouses/ partners) are likely to cause domestic violence against the Filipino wives/partners and children.

Domestic problems in turn lead to divorce. Some divorced Filipinos suffer from lack of financial support for the children from their former husbands/partners. In case they have no children, or do not have custody of the children, they may lose the permission to continue to stay in Japan.

Those who are able to change their residence status and continue to stay in Japan may be deprived of contact with their children if they (children) are in the custody of the Japanese parents.

Some Filipinos suffer from the lax “divorce by agreement” system7 in Japan that allows divorce applications to the local government despite the absence of one spouse. This results in the so-called “unwanted divorce,” divorce without proper consent by one of the spouses. A spouse can file a fraudulent divorce application by using the hanko (personal seal) of one spouse without permission, or by faking the signature of the spouse. A foreigner spouse may also be tricked into signing a Japanese language document without knowing that it is a divorce appli cation. The local government approves the fraudulent divorce application as a matter of course without giving the absent spouse the opportunity to confirm the hanko or signature on the document. The fraudulent divorce application can include a provision on the custody of the children, which can unfairly deprive foreign spouses of the right to have the custody of the children or even contact them.

The approval of the fraudulent divorce application remains valid despite complaint of unauthorized use of hanko or fake signature.8 Affected foreign spouses/partners have to resort to a complicated judicial process to remedy the situation.9

There are reports of rising number of “unwanted divorce.” ATOMS, for example, received 69 “unwanted divorce” complaints of foreigners by end of March 2015 and another 69 similar complaints at the end of the year.10

Before 2008, Japanese-Filipino children born outside of wedlock whose Japanese fathers failed to acknowledge them before they were born were not qualified to become Japanese citizens under Japanese law. However, a Supreme Court decision in 2008 declared the relevant legal provision unconstitutional and violative of the international human rights standards.11 The Japanese parliament (Diet) passed a law in the same year revising that particular provision of the Nationality Law based on the decision of the Supreme Court.12

The 2008 Supreme Court ruling and the subsequent amendment of the Nationality Law opened the door for Filipino parents of Japanese-Filipino children (who either have Japanese citizenship or qualified to apply for it) in the Philippines to come and reside in Japan to take care of the children. So-called “foundations” in the Philippines offered to facilitate their visa application as parents accompanying their Japanese Filipino children to live in Japan. They were also promised jobs to support themselves. Some of these parents were given work in caregiving institutions in Kansai, where they stayed with their JapaneseFilipino children.

Two problems have arisen from this situation: labor exploitation and welfare of the children. A case in Osaka involved long hours of work and numerous deductions from the salary of the parents (mothers). They were even asked to sign a document that exempted the company from any liability in case of death.13 Some of the parents sued the company in court for damages, which ended with a settlement agreement.14

The other problem was on the adjustment of the Japanese Filipino children to a totally new environment. Research on difficulties faced by Japanese Filipino and Filipino children studying in Japanese schools reveals the following:15

(1) Lack of Japanese language proficiency that affects communication with others and learning capacity;

(2) Maintaining relationships with schoolmates who have “unfriendly attitude” to them, keep distance from them after knowing each other, have different ways of getting along as friends, and in some cases bully them or express prejudice against them;

(3) Due to inadequate Japanese language ability, uncertainty about academic future after lower secondary school (junior high school), or worry about capacity to enroll in preferred university course even if they can enter upper secondary school;

(4) Confusion on the different school cultures and rules in the Philippines and Japan leading to actions that are allowed in the Philippines being considered violations of Japanese school rules; some also feel pressured by the strict rules in Japanese schools;

(5) New family environment such as living with parents they had not grown up with and the need to work parttime to help support the family (or themselves) affect their studies;

(6) Use of Filipino and Japanese languages has not led to mastery of any language while learning the Japanese make them lose their proficiency in Filipino and English languages that eventually lead to communication gap with their parents;

(7) Negative view of the Philippines may cause them to hide their Filipino identity, while those who see their Filipino ancestry positively have less worry being so identified. Some of them have trouble following two value systems - Filipino and Japanese.

Older long-time resident Filipino women in Kansai recognize the limitation brought by their inability to read and write in Japanese. Though the jobs (low-paid, part-time work) available to them do not match their academic credentials, they still consider them important. Some have to work to support themselves and/or their family (in Japan and also in the Philippines). Some Filipino spouses/mothers work as the sole income earner in the family because of sick, irregularly employed or deceased Japanese husbands/partners. These women also have to contend with the often negative stereotypes about Filipino women that circulate in Japanese society.16

Other Issues

Filipinos who come to Kansai under the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) are deployed in companies in the different prefectures of the region. Many of these Filipino trainees (officially called technical intern trainees) seem to be working in small- and medium-sized companies. There are reports of abuses by the companies in terms of salary deductions, overtime pay, and working conditions (including long working hours and lack of safety in the workplace). In addition, they have to pay the high cost of accommodation and other needs (electricity and water costs).17

Filipinos who come to Japan to study Japanese language (and caregiving for eventual work in the caregiving industry) can be abused by the “shool” administrators by requiring them to work in order to pay for their supposed expenses. In one case in Kyoto, several Filipinos who paid for their travel to Japan to study were deployed to work beyond the allowed number of hours of part-time work for foreign students. They were also charged high fees for accommodation (15 people in one house) and other costs.

Responses to the Issues

The drastic reduction of the number of entertainer visas issued to Filipinos did not address the exploitation issues (ranging from labor to trafficking problems) that affected them. Neither has there been adequate prosecution of those who committed the abuses in Japan against the entertainers.18

From the 1980-1990 period (when exploitation of entertainers was given more attention) to the present (when issues about Filipinos residing in Japan on long-term or permanent basis are the focus), a number of Japanese NPOs (non-profit organizations) and international centers have been extending support to Filipinos in Kansai. They provide a number of services from consultation service (personal visit or by telephone) to legal and other forms of assistance.19 Filipinos and their children also avail of local government-operated shelters for victims of domestic violence.20

Filipino individuals, communities and organizations provide various types of support to those in need of help; the Philippine Consulate- General in Osaka provides help through its Assistance to Nationals (ATN) program while the Philippine Overseas Labor Office (POLO) in Tokyo provides service to Filipino contract workers including trainees in Japan.

There is still much work to do to stem the tide of issues facing the Filipinos in Kansai. Largely unexpressed in public, Filipinos see the underlying discriminatory attitude against foreigners in the Japanese society as a factor to consider.

Jefferson R. Plantilla is the Chief Researcher of HURIGHTS OSAKA.

For further information, please contact HURIGHTS OSAKA.

Endnotes

1 According to the Japanese government statistics, there were 243,662 Filipinos in Japan as of end of December 2016, see 第6表 都道府県別 年齢・男女別 在留外国人 (その4 フィリピン) [Table 6. Age by prefecture. Foreign nationals by gender (part 4 Philippines)], www.estat.go.jp/SG1/estat/ GL08020103.do? _toGL08020103_&listID=0000 01177523&requestSender=dse arch.

2 The Kansai region is composed of the following prefectures: Mie, Shiga, Osaka, Kyoto, Hyogo, Nara and Wakayama, see “Kansai,” The Government of Japan, www.japan.go.jp/ regions/kansai.html. For the number of Filipinos residing in each prefecture, visit e-Stat, www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/ List.do?lid=000001177523.

3 Information from とよなか国際交流協会 相談事業 (Toyonaka International Association Consultation Project), received by e-mail on 27 October 2017.

4 This list is based on 2015 data supplied by SINAPIS via e-mail dated 27 November 2017.

5 See David McNeil and Chie Matsumoto, “Speaking out about domestic violence,” The Japan Times, 7 November 2009, www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2009/11/07/national/speaking-out-about-domesticviolence/#.WfFBNLpuIdU. See also Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office, Violence Against Women, in Women and Men in Japan 2017, www.gender.go.jp/english_contents/pr_act/pub/pamphlet/women-and-men17/pdf/1-6.pdf.

6 See Anna Fifield, “In Japan, Single Mothers Struggle with Poverty and With Shame,” The Washington Post, 28 May 2017, www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/in-japan-singlemothers-struggle-with-povertyand-with-shame/2017/05/26/01a9c9e0-2a92-11e7-9081-f5405f56d3e4_story.html?utm_term=.784de268cf81.

7 The court route for divorce is also seen as lax because of its “’nontrial’ proceedings, with very loose procedural and evidentiary requirements,” and the lack of power of the courts to enforce their decisions in divorce proceedings. See Colin P. A. Jones, Divorce and Child Custody Issues in the Japanese Legal System, 1 February 2012, https:// amview.japan.usembassy.gov/en/divorce-law-in-japan/.

8 See for example an initiative to prevent this problem from victimizing foreign spouses in RIKON ALERT (Action Group for Divorce by Agreement), https://atoms9.wixsite.com/rikon-alert/english.

9 Kyodo, “Law failing nonJapanese in forced divorces: advisory group,” The Japan Times, 4 March 2016, www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/03/04/national/socialissues/japanese-law-failingprevent-fraudulent-divorcesadvocacy-group/#.WgJiFYhx0dU.

10 Kyodo, ibid.

11 This provision of the Nationality Law had been criticized by the Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) many years earlier for being discriminatory. See Statement on Supreme Court Ruling the Nationality Law Unconstitutional, www.nichibenren.or.jp/en/document/statements/year/2008/20080604.html.

12 The Nationality Law (Law No.147 of 1950, as amended by Law No. 268 of 1952, Law No. 45 of 1984, Law No. 89 of 1993 and Law. No. 147 of 2004, Law No. 88 of 2008). Source: Ministry of Justice, http://www.moj.go.jp/ENGLISH/information/tnl-01.html.

13 “Japan firm obliges Filipino workers to waive its responsibility for deaths,” South China Morning Post, 13 July 2014, www.scmp.com/news/asia/article/1553177/japan-firm-obliges-filipinowomen-waive-itsresponsibility-deaths.

14 “Nursing care firm to compensate 10 Filipino ex-staff over harsh working conditions,” Mainichi Japan, 3 February 2017, http://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20170203/p2a/00m/0na/020000c#csidx3336a2bd39de6ec8b3f72be718c6804.

15 List provided via e-mail on 11 November 2017 by Kimi Yamoto, based on her research on the school education of Japanese-Filipino and Filipino children and on the support she has been providing to them in public schools for many years.

16 Michelle Gedang Ong, Growing old in an ageing Japan: Filipina migrants’ experiences and meaningmaking (2016) (draft).

17 Masami Ito, “Foreign trainee system said still plagued by rights abuses,” The Japan Times, 9 April 2013, www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2013/04/09/reference/foreigntrainee-system-said-stillplagued-by-rights-abuses/#.WfKLbohx0dU; Kentaro Iwamoto, “Abuses rampant in foreign trainee program, Japan labor ministry finds,” Nikkei Asian Review, 18 August 2016, https://asia.nikkei.com/PoliticsEconomy/Economy/Abusesrampant-in-foreign-traineeprogram-Japan-labor-ministryfinds; Mainichi Japan, "Editorial: Prevent abuses of foreign trainee program," 28 November 2016, http://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20161128/p2a/00m/0na/021000c. Watch also this video: “Used and abused: Japan's foreign trainees,” France 24, 2017-06-09 www.france24.com/en/20170609-focus-japan-foreigninterns-technical-traineesimmigration-labour-law-abuseexploitation. See also China Labour Bulletin, Throw Away Labour - The exploitation of Chinese "trainees" in Japan (Hong Kong, 2011), Institute for Human Rights and Business, Learning Experience? Japan's Technical Intern Training Programme and the Challenge of Protecting the Rights of Migrant Workers, October 2017, www.ihrb.org/focusareas/mega-sporting-events/japan-titp-migrant- workersrights.

18 See “Japan- 2017 Trafficking in Persons Report,” US State Department, www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2017/271213.htm and for statistics on number of “cleared cases” and persons arrested on trafficking charges see Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office, 6. Violence against Women, Women and Men in Japan 2017, page 16, www.gender.go.jp/english_contents/pr_act/pub/pamphlet/women-and-men17/pdf/1-6.pdf.

19 See "Breaking the Barrier: Japanese NGOs Take Up the Challenge," FOCUS Asia-Pacific Newsletter, Volume 5, September 1996, www.hurights.or.jp/archives/focus/section2/1996/09/breaking-the-barrier-japanesengos-take-up-thechallenge.html.

20 The 2001 Law on Prevention of Spouse Violence and Protection of Victims required the government to establish facilities to help domestic violence victims. See Miriam Tabin, “Domestic Violence in Japan - Support Services and Psychosocial Impact on Survivors,” FOCUS Asia-Pacific Newsletter, Volume 70 December 2012, www.hurights.or.jp/archives/focus/section2/2012/12/domestic-violence-in-japan---support-services-andpsychosocial-impact-on-survivors.html.