- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- March 2018 - Volume 91

- Gaokor: When Will This Life-threatening Custom End?

FOCUS March 2018 Volume 91

Gaokor: When Will This Life-threatening Custom End?

She had been living in the run-down hut on the outskirts of a tribal village, barely seven kilometers from Gadchiroli, Maharashtra State, for the past four days. She was not allowed to enter the village. She was an untouchable to everyone in the village, including her entire family. Despite the deathly cold, this fourteen-year old girl spent the last four nights in the ramshackle, doorless hut with just a tattered mat and blanket.

What did she do to deserve this? What crime did she commit that she had to face the life of an outcast?

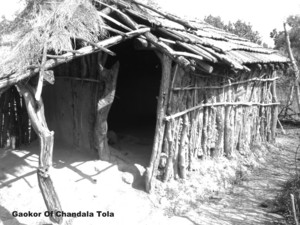

According to the custom of the Madiya and Gond tribals in Maharasthra state, girls having their menstruation period have to stay in a hut on the boundary of the village as their touch is considered impure. These huts are called gaokor.

The Issue

Menstruation is nature’s rule. It starts in women around the age of twelve and continues till menopause, which occurs between forty-five to fifty-five years. This monthly occurrence, which is part of the process of reproduction, is a difficult time for women (especially young girls) who need care since blood loss in large quantity leads to exhaustion. They need mental as well as physical support. Living in the gaokor in this difficult time can be a life-threatening situation for hundreds of tribal women and girls.

Two years ago, during the monsoons, a young girl lost her life in the Bhamragad district due to excessive loss of blood. She could not get any medical aid in the gaokor which was outside the village. Not only is the time spent in the gaokor dangerous to the health of girls and women, it is also unsafe. In November 2015, a girl was carried away by a wild animal. More incidents of drunkards harassing girls and women living in gaokors have been reported.

In villages with large population, women have company during their time in the gaokor. In the past, old women stayed with the women living in the gaokor. But the reality today is that such old women are absent in most villages.

A girl who graduated from secondary school (12th year of schooling) came to the Mannerajaram primary healthcare center and narrated her experience:

We are forbidden from walking on any village road during this period. I have an old mother and alcoholic brother. Many times, the food doesn’t reach me on time. We cannot go into the village even if we are starving. The monthly period is a law of nature. This is my fate. My education is of no use here.

As she said this, her eyes teared up with sheer frustration as she realized that she could not do anything to change the situation. The head of the tribal youth group of the Chandali Toli said, “Even the sight of a woman who has her monthly period is inauspicious for us after we have a bath.”

“It is our duty to preserve this custom that has been going on since a long time,” said the deputy Sarpanch (village head) of the neighboring village. When told that the tribal women who live in the city do not stay in the gaokor during their monthly period, he said, “It is because of such people that our culture is being destroyed.”

Women do not sit idle even during her monthly period if they stayed at home. They will find some work to do. Some people say that the gaokor is meant to force the women to take a rest. But how can the women rest by staying in an ill-equipped, doorless, isolated hut? People who support the gaokor custom do not have an answer to this question. Some people in the community firmly believe that the utensils, clothes and other things become “impure” if the women with menstruation touch them, thus staying outside the house is the best arrangement. However, they cannot give a concrete reason for not allowing the women to walk on the street.

Gaokor

A study by SPARSH of around 225 gaokors in five tribal bahul (tribal dominated) villages revealed their pathetic condition. Most have a single window for light and no door. Almost all gaokors are on the border of the village, and more often than not at the edge of a dense forest. Their surroundings are astoundingly unclean. Among the most basic necessities in the gaokor is a small pot for drinking water, a temporary bathroom built using banana leaves for bathing and a broken bed, if at all, along with threadbare sheets for sleeping.

The community owns and maintains the gaokors. But the influence of cities among the tribals led to the neglect of the gaokors. Only a handful of gaokors are taken cared of collectively.

Government Response

The government of India has a program for the integrated socio-economic development of the Scheduled Tribes (STs). Funds are provided to state and local governments for this purpose.

In the town of Gadchiroli in Maharashtra state, the local government using the funds from Ekatmik Tribal Vikas Prakalp (Integrated Tribal Development Scheme, Gadchiroli) implemented a project in March 2017 to improve a hundred selected gaokors. Hundreds of thousands of Indian Rupees were spent to buy plates, bowls, drums for water, mats, cabinets, etc. for the gaokors. However, due to the usual lack of authorization, coordination and information, the purchased items failed to reach the gaokors and ended undistributed in the offices of district administrators and the Adivasi Vikas Vibhag (Tribal Development Department).

This case illustrates the wrong reason for the government scheme of refurbishing gaokors. The girls and women during the period of menstruation need support from their family. The primary concern is the maintenance of their good health. But this concern is not yet in the thinking of people in tribal communities. They still do not see the problem that any form of improving the gaokor custom (such as by refurbishing them) strengthens this appalling custom. While improving the condition of the gaokors can be a first step towards change, without schemes to change people’s mentality any developmental initiative will only result in waste of funds.

SPARSH filed a complaint on this issue on 10 July 2013 with the National Human Rights Commission of India (NHRC), urging its intervention in the matter and the issuance of necessary directives to the concerned authorities.

The NHRC directed the Chief Secretary of Maharashtra state to “look into the matter and sensitize the concerned officer about the gross violation of human dignity and human rights of the affected women...” The state government formed a Committee on 26 December 2014 to study the gaokor issue and find out necessary measures to eradicate the gaokor custom. The then Deputy Secretary of Tribal Development Department informed the NHRC in February 2015 that a Committee had been formed under the leadership of a District Collector. The structure of the Committee was also mentioned in his report. But the Committee had actually never existed.

In 2017, the NHRC directed the Chief Secretary of Maharashtra state to inquire into the matter and to take appropriate action against the concerned officials for not convening the meeting of the Committee formed by the government and filing a wrong report to the Commission.

Taking a serious note of the lapse, it also asked the Chief Secretary of the Tribal Development Department to appear before it in person on 20 December 2017 and produce the required information and documents. The NHRC issued another directive on 16 January 2018 and criticized the government for its continuing ignorance on this deadly issue.

Future

On 15 November 2017, Jayanti Baburao Gawde, 40, went to sleep in the gaokor. Jayanti was lucky that night because she was accompanied by a girl who was also on her period. The next morning, the girl woke up and went home, but Jayanti did not stir. Jayanti was later rushed to the hospital and was declared dead on arrival. High blood pressure was reported as the cause of her death. The villagers felt that she could have been saved had she stayed with her family. Jayanti was from Etapalli Tola, of Etapalli Block, in Gadchiroli district. Etapalli block’s medical officer, Dr Pavan Raut, noted the unhygienic conditions in the kurma ghar (literally, period house):

The unhealthy practices adopted by tribal women during their menses lead to various RTI [reproductive tract infections]. The scruffy environment of Kurmaghar creates more pathetic condition. The problem also lies in the fact that they don’t want to visit the hospital for treatment.

The tribals have a prosperous culture, rich enough to make urban society bow its head in shame. The tribal culture has several good practices and traditions. But, the gaokor custom is a blight on the adivasi (tribal) culture. These proud tribals need to be informed in confidence about the harm the gaokor custom causes.

SPARSH, which has been doing a lot of work in this area including interactions with the women, found that at least some people from the Madia and Gond communities have accepted the fact that the gaokor custom is harmful. But they do not dare give up the custom for fear of ostracization. SPARSH has reached the conclusion that it is impossible to suddenly end this practice because of the strong beliefs of the tribals. The least that can be done is improve the living conditions of the gaokor for the meantime. It is heartening to know that there are a few tribals who are working for this cause.

While an Indian-origin astronaut Sunita Williams has left an indelible mark in the field of science through several successful space missions, thousands of Indian tribal women have to live in life-threatening conditions created by the atrocious gaokor custom.

Till today neither the government nor any social welfare organization has taken up the gaokor problem. The important question is: when will people wake up and recognize this problem?

Dilip Barsagade, PhD, is the President of SPARSH, Gadchiroli.

For further information, please contact: Dilip Barsagade, SPARSH, Keshawsut, Snehanagar, Dhanora Road, Gadchiroli, Maharashtra, India, 442605; cellphone :( +91) 9422152617, 9922387724; e-mail: dkbarsagade[a]gmail.com.