- TOP

- 国際人権基準の動向

- FOCUS

- June 2018 - Volume 92

- Orang Rimba: Endangered People in Endangered Forest

FOCUS June 2018 Volume 92

Orang Rimba: Endangered People in Endangered Forest

In 2014, an Indonesian photographer described the Orang Rimba in the following manner: 1

Orang Rimba is one of the tribe groups living in the depth of forests in Jambi Province (Sumatra, Indonesia). They lead what to some may seem a unique lifestyle owing much to the values and traditions they espouse, which are traced back many centuries ago. The uniqueness in value systems they hold is reflected in their traditions, food they eat, shelters they use to serve as housing, and methods they employ in cultivation. What is most outstanding in their livelihood is the importance they attach to forests, which is the provider of everything to sustain their lives. To them life follows the cycle of nature, mutually beneficial to all elements, humankind, animate and inanimate alike.

It is believed that around 3,500 members of the Orang Rimba live in the Bukit Dua Belas National Park in Jambi province.2 But the continuing destruction of the forest in the park to give way to palm plantations and other agricultural activities has endangered the livelihood, culture and social organization of the Orang Rimba.

Forest Laws

The Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (AMAN) or Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago reported in 2017 to the Human Rights Council3 that the 1999 Indonesian Forestry Law legalized land-grabbing and converted customary forests into state forests. Under this law, the Indonesian government granted concessions to “private companies for mining, logging and plantations in indigenous peoples' traditional lands in violation of their rights. ”The 2014 Law on the Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction, on the other hand, “criminalized indigenous peoples living within national parks, protected forests and wild life reservation.”

AMAN pointed out that the Indonesian Constitutional Court4 declared in 2012 that these two laws violated the indigenous peoples' rights. However, these laws have not yet been “amended in order to ensure [the protection of] the rights of indigenous peoples.”5

An Educational Response: Pencil as Evil

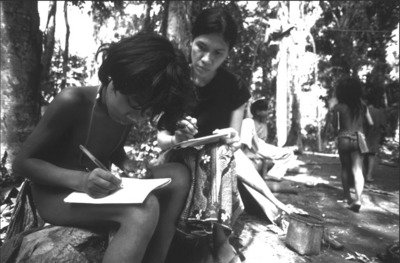

Saur Marlina Manurung (popularly known as Butet) started to support the Orang Rimba in 1999, as a member of a conservation group (WARSI),6 by teaching the indigenous children how to read and write. She narrated how the Orang Rimba would see the pencil as “evil with spiked eyes” since they “had been cheated out of their land when they were made to sign contracts under false terms.” Her effort to teach the children on how to read and write was rejected by the community. But she persisted and in the 7

seventh month, her efforts reached a turning point. Three boys went to her. They were 7, 10, and 14 years old and they wanted her to teach them. Seven year old Pendengum Tampung, when he succeeded in reading the word “buku” which means “book” in Bahasa Indonesia, climbed a tree and started screaming to the whole forest, “I can read!” Ten years later, she would witness Pendengum, now a young man, addressing a crowd of hundreds about the human rights of forest people.

She was not confident at the beginning about the wisdom of her educational initiative:8

When she started her literacy campaign, she had to ask herself whether the Orang Rimba really needed change and whether this change would preserve or destroy their culture. She realized that her first task was to make them feel proud of themselves, to help them realize that what they have in the jungle is complete and is of value. She believes she has succeeded in this because none of her students leave their home.

Proper Pedagogy

Butet started her “’school for life,’ a school that benefits … the Orang Rimba directly,” adopts their perspective and deals with real situations in life. She learned to respect the views of her “students” who once told her not to stop them from killing a baby bear caught in a trap. They explained:

Ma’am, please don’t say that. If God heard you, he would not send food anymore. What’s in our trap, what’s in front of us, that is food sent by God.

She describes the “school for life”:9

My school is not like a regular school. Whenever you have a problem, you make a school for that. If you have a problem with logging, you learn how to chase them away. If you have a problem with diarrhea, you find the sources of information so you can combat diarrhea and teach the community.

The effectiveness of her pedagogy is seen in the following report:10

The children influence Butet and teach her invaluable pedagogic skills. She starts where they are. She […] keeps it simple and fun. Far from a rigidly prescribed curriculum, she adopts an organic non-judgmental approach, inventing her own teaching techniques in the field. Realizing that kids learn the sounds of letters first and then their shapes, she develops a practical reading-writing-counting syllabic method. Butet eventually lets her students teach one another. Surprising results follow. After three months, she takes her best students to other locations to become teachers. When asked what they want to be, many children reply, “a teacher trainee.”

SOKOLA

In 2003, Butet started with several like-minded people a non-governmental organization named Sokola which developed “literacy programs that are responsive to the strict customs, traditions, lifestyles, and development challenges of indigenous and marginalized communities.” Through the years, Sokola expanded by establishing fourteen schools with “eighteen teachers, and thirty volunteers” serving indigenous communities in “ten provinces across Indonesia, including Nanggroe Acheh Darussalam, Jambi, West Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, Flores, the Mollucas, and Papua [and involving] ten thousand children and adults.”11

Butet noted that “many of her former students are now community leaders and teachers themselves, including Pengendum, the boy who celebrated reading his first word by climbing a tree.”12

Butet was the recipient of the 2014 Ramon Magsaysay Awards for her “ennobling passion to protect and improve the lives of Indonesia’s forest people, and her energizing leadership of volunteers in Sokola’s customized education program that is sensitive to the lifeways of indigenous communities and the development challenges they face.”13

For further information, please contact HURIGHTS OSAKA.

http://rmaward.asia/awardees/manurung-saur-marlina/.

www.aman.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/INDONESIA_AMAN_AIPP_UPR_3rdCycle.pdf.

www.baliadvertiser.biz/the-jungle-school-by-butet-manurung/.