- TOP

- 国際人権基準の動向

- FOCUS

- September 2019 - Volume 97

- Remembering the Past: Henomatsu Community

FOCUS September 2019 Volume 97

Remembering the Past: Henomatsu Community

Henomatsu community is the only Buraku community in Sakai city in the Osaka prefecture in Japan. Up until the 1960s, the people in Henomatsu community were suffering from poverty, poor housing conditions, and lack of facilities such as water supply. These problems were the result of discrimination against them as Buraku people.

The word Buraku means a village or a hamlet in Japanese language. Since feudal age, people in some communities in Japan had been classified as outcasts, outside the social hierarchy, which was closely related to the caste system. These communities became known as Buraku communities. Even in the modern age, people living in, or from Buraku communities, or are descendants of such people may be regarded as Buraku people by ordinary people and may suffer from discrimination, exclusion, etc., especially in marriage and employment. Cases of hate speech against Buraku people and identifying people as Buraku through the internet have arisen in recent years in alarming number that led to the new enactment of a law in 2016 to promote the elimination of Buraku discrimination.1

The enactment of the 1969 Law for Special Measures for Dowa Projects to alleviate the conditions in the Buraku communities all over Japan brought changes to the Henomatsu community.

The 1969 law provided funds to local governments to redevelop the Buraku communities in many urban areas.

This law had a ten-year period and then extended for another three years – 1969 to 1981. This law was followed by other laws that extended the support for the renewal of Buraku communities to twenty-seven years. A report explains the laws:2

[The 1969 special measures law] was followed by a 5-year term new law called the ‘Special Measures for Area Improvement Projects Law’, which was in force from 1982 to 1986. A minor change in the law’s title followed in 1987, and this renamed ‘Law for Special Fiscal Measures for Area Improvement Projects’, initially enacted for 5 years, was once again extended by another 5 years to 1996. As of March 31, 1997, if the ongoing Dowa projects were not completed, at most another 5 years of financial support was guaranteed.

The local governments played an important role in implementing these laws in their respective areas in collaboration with the national government. Sakai city actively implemented these laws in the Henomatsu community.

Nishiko Sakamoto: Preserving the Past

Nishiko Sakamoto was a woman leader in the Henomatsu community. She realized that her community had started to change because of the 1969 special measures law in ways that would erase the memory of its past conditions. The law was bringing radical changes in the housing and physical conditions of the Henomatsu community.

Sakamoto advocated for the preservation of the history of Henomatsu community – by recording the situation before the changes occurred in the 1970s in the community.

She saw the need to start collecting materials in the 1980s. She convinced the community organization, the local chapter of the Buraku Liberation League (BLL), to support her idea. She was also able to get the support of other people outside the community including academics to help in the documentation process.

In late 1980s, BLL started a series of publications that present the history of Henomatsu community. This publication is entitled “Shashin ni Miru Kyowa-cho, Kurashi no Monogatari - Kyoiku, Undo” (Kyowa-cho: Story of Life in Photos - Education and Movement). It is also known as the red book because of its red-colored cover.

Henomatsu Community Center

The Sakai city government constructed a seven-floor building in the Henomatsu community in 1974 to serve as the community center for the people in the area. The building had facilities for sports, cultural and social activities. When a room in this building became vacant, Sakamoto was able to get the permission to use it as the place where documentation materials (documents, photos, magazines and books) about the Henomatsu community could be stored and processed.

Henomatsu Community Center building, 1974

As years passed, the materials collected grew in significant number. This led to the idea of establishing a museum that would present the history of Henomatsu community to the general public.

Henomatsu Human Rights History Museum

The Henomatsu Human Rights History Museum was inaugurated in 1998 as the repository of materials on the history of the Henomatsu community. It also displays materials pertaining to the Buraku liberation movement. The text of the 1922 Suiheisha Declaration,3 which speaks of the human rights of the Buraku people, carved in marble slabs, was displayed in the museum.

The Henomatsu Community Center building was demolished in 2014 and a new building was built in 2015 to house the museum and other facilities. The museum currently consists of three parts: Henomatsu community history, Sankinchi Sakata Memorial Hall and human rights library.

The history section displays old photographs of the community as well as replicas of the small one-room houses of the people, the communal toilet, communal water faucet, and models of people inside their house and those working in the leather industry in the community.

Museum guides explain to visitors the stories about the displays such as the spread of an eye disease in the community that led to the establishment of a medical clinic, the impact of the transfer of factories to a nearby area which refused to hire people from the community because of their status as Buraku people and the drying up of the traditional community wells because of the water pumps of the factories. When the wells dried up, the people in the Henomatsu community pooled their money to have a communal water faucet because they could not afford to have water supplied to their houses.

Portrayal of people working in the leather industry in Henomatsu community

The history section likewise presents the story of the local anti-discrimination movement. It provides information on the different historical events of the movement and the people involved.

Henomatsu Human Rights History Museum

The human rights library has all types of written materials about the Henomatsu community.

The Sakata section exhibits the shogi board and other materials used by the Sankichi Sakata. A Sakai city website describes Sakata in the following manner:4

Born in Henomatsu-mura, a village in Otori-gun, Sakata Sankichi memorized the Japanese game of shogi (Japanese chess) while watching it played by adults in the alleyways of his youth. He exhibited an almost miraculous strength in the game, deploying richly imaginative moves whose potential vastly exceeded the more conventionally accepted playbook. He was extremely successful in the achievement-based world of competitive shogi, and he came to typify the times along with Sekine Kinjiro, whom he considered a worthy opponent.

In 1955, he was posthumously awarded the ranks of Master and King by the Japan Shogi Association.

The Henomatmatsu Community Center is being managed by JSA, a group consisting of three non-profit organizations, namely, Sakai City Jinken Kyokai (Human Rights Association), Sakai City Shurou Shien Kyokai (Job Assistance Association) and ALL (Human Rights Advance Sakai). JSA has secured a contract to manage the center from the Sakai city government.5

Henomatsu Community Landmarks

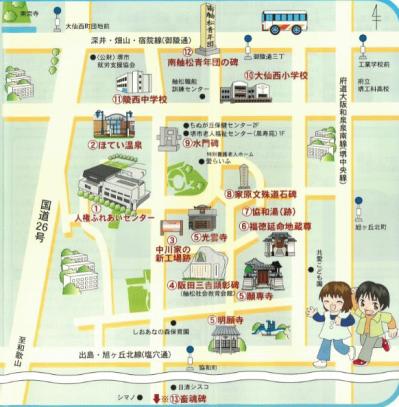

The Henomatsu community also ensured that different places where historical events happened are properly marked for people to remember and learn from. Thus, various places in the community have signs that explain historical information such as an old stone marker that tells people not to make the mistake of using the foot path that leads to the Buraku community, the place of a public bath where members of the community gathered to discuss community issues, another place of a factory building where members of the community held activities, and the place where the small house of Sankinchi Sakata family stood before. Being a member of the community, Sakata is given honor for his achievement.

The Henomatsu Center promotes a tour of the community to enlighten people on its history.

Pamphlet showing the different parts of the Henomatsu community with historical landmarks

The renewal of the Henomatsu community was not only a matter of improving its physical conditions but includes measures that ensure that the suffering and the efforts of the people in the community to end their problems are remembered and known to the general public.

Jefferson R. Plantilla is the Chief Researcher in HURIGHTS OSAKA.

Kazuhiro Kawamoto is a Program Officer of the Buraku Liberation and Human Rights Research Institute.

For further information, please contact: HURIGHTS OSAKA.

Endnotes

1 See HURIGHTS OSAKA, “Law Against Buraku Discrimination,” FOCUS Asia-Pacific, March 2017, volume 87, www.hurights.or.jp/archives/focus/section3/2017/03/law-against-buraku-discrimination.html.

2 Toshio Mizuuchi and Hong Gyu Jeon. "The new mode of urban renewal for the former outcaste minority people and areas in Japan," Cities, 2010, doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.03.008, pages 3 – 4, www.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/geo/mizuuchi/japanese/material/mizuuchi_jeon_Cities.pdf.

3 For the full text of the 1922 Suiheisha Declaration, visit Human Rights Declarations, www.hurights.or.jp/english//declarations-in-the-asia-pacific.html.

4 "Sankichi Sakata,” www.city.sakai.lg.jp/english/visitors/whats/notable/sakatasankichi.html.

5 See website in Japanese language of the Henomatsu Community Center (managed by the JSA) for more information, https://jinken-fureai.jp.