- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- December 2021 - Volume 106

- Color Vision Diversity - Towards Wider Recognition of Color Vision Minority

FOCUS December 2021 Volume 106

Color Vision Diversity - Towards Wider Recognition of Color Vision Minority

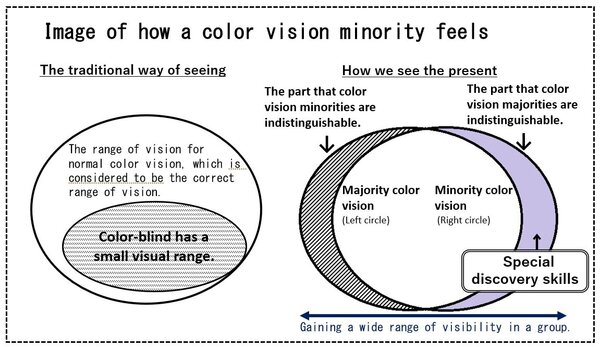

The current medical term "achromatopsia" or the former term "color-blindness" is understood by many people as "inferior color vision" or an "inability to distinguish colors." To explain the condition, I use the term, "minority color vision" or the person with the condition, "color vision minority." It is a condition or people with a condition that may make it difficult to distinguish between particular colors, but enables discovery of things that many people may be missing.

Research in color vision or sensation has made tremendous progress in the 21st century revealing that color vision of human species was an aspect of its diversity. Discoveries were made in color visions of species other than humans as well. Color vision diversity is also found in New World monkeys living in Central and South America. Professor Shoji Kawamura of Tokyo University confirmed that monkeys with minority color vision were not inconvenienced by their conditions in fruit foraging. On the contrary, they were adept at finding camouflaged insects and small animals for food, and these special skills in locating food further increased in the dark. This suggested that it was advantageous to have minority color vision in the group.

School Tests and Education

Later, through development of civilization, human beings were able to create colors, classify them, put names on them and use them as a means of communication. People subsequently realized that there were some who found it difficult to distinguish some colors which many other people did with ease. Since around the end of the 19th century when the colors red and green were adopted for railway signals, the condition was considered problematic, as "it was dangerous when someone cannot distinguish the signal colors," and color-blind tests were introduced. In those days, a color-blind person meant "a person with color vision that should be excluded from railway operations." Strict tests were conducted and people with the condition were excluded from railways and shipping.

At the beginning of the Meiji era, Japan introduced the color-blind test along with the railway and testing was started following the western practice. During this period, under the slogan of creating a "rich country, strong army" and with the rise of the eugenics ideology people were placed in a hierarchical order and groups of people were created and excluded, such as people with Hansen's disease. Color vision minorities, who until then were unnoticed, were labeled "people with inferior color vision," and were deemed unqualified for any job that involved colors. Everyone in the country was required to be tested for color-blindness before choosing their occupation, and the system of testing all children in the former primary school started in 1921. The test not only led to the exclusion of color vision minorities, but also to the reproduction and spread of misperceptions regarding color vision.

The testing system continued after World War II, and the misperceptions were taught in detail in school. In the 1950s, a Japanese junior secondary school textbook on health and physical education used a genetic diagram to explain "how a color-blind boy is born from non-color-blind parents." The female genetic carrier would be explained as being "healthy in appearance," and the textbook admonishes readers to do a background check before marriage on the intended bride. Because people with these conditions may "reduce the efficiency of the occupation and harm social development" when they take up an inappropriate employment, the textbook gives a list of "unsuitable occupations."

Since the Meiji era, these teachings were taught among teachers, doctors as well as at home, and even today quite a number of people still believe that people with anomalous color vision are those "who perceive red and green as identical colors," "who are ineligible for a driver's license," or "who have a rare abnormality." Since then, people with achromatopsia increasingly faced policies such as exclusion from employment in the public service, ineligibility for various qualifications, refusal of employment in companies and of enrolment in schools. By the end of the 20th century, Japan became an extremely intolerant country for color vision minorities that was unparalleled in the world.

In Europe and North America, minority color vision is considered "an extremely limited difference" and there are no prejudices or perceptions of being "inferior." A famous British expert on color vision explained to a mother who brought her child out of concern for color vision that the test showed that child had hereditary color vision. The mother said, "So, it is something I inherited from my father. That is why the child has difficulty with some colors. I understand," and she left reassured with no negative perceptions about the difference in color vision. It is very different from Japan.

Abolition and Reintroduction of Uniform Testing

In 2001, the government declared that the majority of those who have been diagnosed with anomalous color vision was not disadvantaged in their work by their condition, and that there were many cases of enterprises unnecessarily restricting their employment. The color vision test was dropped from the required testing items in the health examination before employment, finally putting a curb on the spread of the misperceptions. The uniform testing in schools was abolished in 2003.

However, calls for testing in schools reemerged around 2014. The Ophthalmologists Association argues that tests in schools are "a good opportunity to inform the children about occupations that are currently restricting hiring of color-blind people," and that early guidance should be provided for children with the "abnormality." The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology changed course in that direction, and issued a confusing notice saying that although color vision tests were abolished, the Ministry recommended getting tested. The notice was understood as an order, and since 2016, recommendations for tests spread rapidly nationwide. Children and their parents were tested without any understanding about color vision diversity.

The method used for testing is the well-known Ishihara Test plates. It was a globally acclaimed testing method that could identify anomalous color vision with high accuracy at the time when it was believed that "even people suspected with color-blindness should be excluded." But the method also identifies people with color vision that is not very different from the majority population. The reasons for abolishing the tests are being forgotten, and many people are given career guidance based on the test results alone. As expected, I received reports of many tearful parents and children having been diagnosed as "abnormal" and given guidance.

Fair hiring standards are founded on providing wide access to employment to applicants. Occupational aptitude assessments should be conducted on the abilities necessary for the work. Aptitude tests for pilots using computer analysis for assessment have been developed overseas. It is said that the results may be completely different from those using test plates.

Also, career guidance is something that should be provided systematically in the course of education in a manner appropriate for the various developmental stages, and it is problematic when it is given focusing on one particular physical characteristic. In particular, primary school children for whom it is too early to choose an occupation should not be diagnosed as being "abnormal" and be given career guidance based on the diagnosis. It will mean denying the possibility of review or improvement of the current employment restrictions and making them accept these restrictions unconditionally. This goes against the ideals of the Act for Eliminating Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities enacted in 2016, when the tests were being reintroduced, and would lead to a violation of the freedom to choose an occupation protected by the Constitution.

Shikikaku Gakushu (Color Vision Learning) Color Mates

Because of the above situation, there are many angry voices calling for an end to the tests themselves and the test plates. But it is inconceivable that the misperception and social division regarding color vision minorities in this country will disappear just by abolishing the tests. Indeed, it took little more than ten years after they were abolished that the color-blind tests were swiftly reintroduced. There is a deep-rooted perception that these tests are necessary. "Normal color vision" is still required by law for train driving license in Japan and diagnosis is still being done using only the test plates.

The deeply rooted misperception will not vanish when left alone. Teachers and former teachers have come together to create teaching materials for children and parents to learn about differences in color vision and tests before they receive notices for tests from the school and decide whether to take them or not. This group is the Color Mates. Believing that it is the children and their parents that are in most need of accurate knowledge, we published two kinds of comic books at our own expense (はじめて色覚にであう本 /Hajimete Shikikaku ni Deau Hon [First Encounter with Color Vision] and 検査のまえによむ色覚の本 /Kensa no Mae ni Yomu Shikikaku no Hon [Booklet on Color Vision to be Read Before Testing]).

In July 2021, we translated a children's book published in the United States, ERIK the RED sees GREEN - A Story about Color Blindness[1] and published it asエリックの赤・緑/Erikku no Aka / Midori.[2] The book is about the protagonist with minority color vision finding solutions to his life together with his classmates. It also has explanatory comments for parents. We hope you will pick it up and read it.

Hiroaki Oie has color vision condition. He is a former secondary school teacher and the representative of Shikikaku Gakushu Color Mate.

For further information, please visit: Shikikaku Gakushu Color Mate, https://color-mate.net/ (in Japanese language only).

Endnotes

[1] Authored by Julie Anderson and David Lopez (Albert Whitman & Company, 2013).

[2] Watch video about the book at https://color-mate.net/book.