- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- December 2022 - Volume 110

- Right to Information in India: Information Commissions

FOCUS December 2022 Volume 110

Right to Information in India: Information Commissions

India was ravaged by the deadly second wave of the COVID 19 pandemic in 2021. As per official figures, the virus claimed around five lakh (500,000) lives, though studies and reports by investigative journalists estimate a much higher toll.[1] The public health system, unable to cope with the scale of the pandemic, collapsed resulting in oxygen shortages and non-availability of beds and essential drugs. Lockdowns imposed by state governments led to largescale loss of livelihoods, especially for those in the unorganized sector. The poor and marginalized were the worst affected. Relief and welfare programs funded through public money became the sole lifeline of millions who lost income-earning opportunities after the lockdowns imposed in 2020 and 2021. The crisis clearly established the vital need for transparency in public health, food and social security programs. It became evident that if people, especially the poor and marginalized affected by the public health emergency, are to have any hope of accessing their rights and entitlements, they need to have access to relevant and timely information.

The pandemic underlined the need for proper implementation of the Right to Information (RTI) Act, which empowers citizens to obtain information from governments and hold them accountable for delivery of basic rights and services.

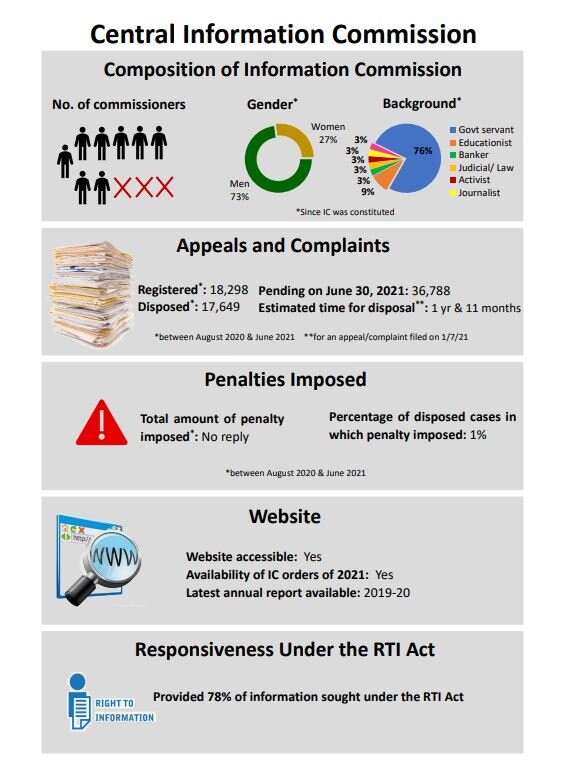

Estimates suggest that every year forty to sixty lakh (4,000,000-6,000,000)[2] RTI applications are filed in India. Under the RTI Act, information commissions (ICs) have been set up at the central level (Central Information Commission) and in the states (State Information Commissions). These commissions are mandated to safeguard and facilitate people's fundamental right to information. Consequently, ICs are widely seen as being critical to the RTI regime.

ICs have wide-ranging powers including the power to require public authorities to provide access to information, appoint Public Information Officers (PIOs), publish certain categories of information and make changes to practices of information maintenance. They have the power to order an inquiry if there are reasonable grounds for one, and also have the powers of a civil court for enforcing attendance of persons, discovery of documents, receiving evidence or affidavits, issuing summons for examination of witnesses or documents. Section 19(8)(b) of the RTI Act empowers commissions to "require the public authority to compensate the complainant for any loss or other detriment suffered." Further, under section 19(8) and section 20 of the RTI Act, they are given powers to impose penalties on erring officials, while under Section 20(2), ICs are empowered to recommend disciplinary action against a PIO for "persistent" violation of one or more provisions of the Act.

Effective functioning of ICs is crucial for proper implementation of the RTI Act. In a judgment dated 15 February 2019, the Supreme Court[3] held that ICs are vital for the smooth working of the transparency law: "24) ......in the entire scheme provided under the RTI Act, existence of these institutions [ICs] becomes imperative and they are vital for the smooth working of the RTI Act."

Sixteen years after the implementation of the law, experience in India, also captured in various national assessments on the implementation of the RTI Act,[4] suggests that the functioning of ICs is a major bottleneck in the effective implementation of the sunshine law. Large backlog of appeals and complaints in many ICs across the country have resulted in inordinate delays in disposal of cases, which render the legislation ineffective. ICs have been found to be extremely reluctant to impose penalties on erring officials for violations of the law. An assessment of the working of ICs across the country during the first phase of the pandemic showed that twenty-one of the twenty-nine ICs were not holding any hearings as of 15 May 2020, even after the national lockdown had been eased and only seven ICs made provision for taking up urgent matters or those related to life and liberty during the period when normal functioning was affected due to the lockdown.

Amendments to the RTI Act and Rules

Recent amendments to the RTI Act have taken away the protection of fixed tenure and high status guaranteed to the commissioners under the law, thereby adversely impacting the autonomy of ICs. One of the most critical parameters for assessing the efficacy of any transparency law is the independence of the appellate mechanism it provides. Security of tenure and high status had been provided for commissioners under the RTI Act of 2005 to enable them to function autonomously and direct even the highest offices to comply with the provisions of the law. Their tenure was fixed at five years. The law pegged the salaries, allowances and other terms of service of the Chief and commissioners of the Central Information Commission and the chiefs of state commissions at the same level as that of the election commissioners (which equals that of a judge of the Supreme Court).

The RTI Amendment Act[5] which was passed by Parliament in July 2019, and the concomitant rules[6]promulgated by the central government, has dealt a severe blow to the independence of ICs. The amendments empower the central government to make rules to decide the tenure and salaries of all commissioners in the country.

The RTI rules, prescribed by the central government in October 2019, reduced the tenure of all information commissioners to three years. More significantly, Rule 22 empowers the central government to relax the provisions of the rules in respect of any class or category of persons, effectively allowing the government to fix different tenures for different commissioners.

The rules do away with the high stature guaranteed to commissioners in the original law. A fixed quantum of salary has been prescribed for the commissioners - Chief of CIC at Rs. 2.50 lakh per month and all other central and state information commissioners at Rs. 2.25 lakh per month. By removing the equivalence to the post of election commissioners, the rules ensure that salaries of information commissioners can be revised only at the whim of the central government. Again, the government being empowered to relax provisions related to salaries and terms of service for different categories of persons, destroys the insulation provided to commissioners in the original RTI Act.

The autonomy of commissions has been further eroded by enabling the central government to decide certain entitlements for commissioners on a case by case basis. The rules, which are silent about pension and post-retirement entitlements, state that conditions of service for which no express provision has been made shall be decided in each case by the central government. The power to vary the entitlements of different commissioners could easily be used as a means to exercise arbitrary control and influence. These amendments could potentially make commissioners wary of giving directions to disclose information that the central government does not wish to provide.

How Transparent are the ICs?

Satark Nagrik Sangathan has been undertaking assessments of the various aspects of the implementation of the RTI Act in India. Every year, since 2018, a report on the performance of ICs in the country is published. The 2020 assessment report titled Report Card of Information Commissions in India 2020-21 looked at the performance of ICs in terms of providing information to citizens about their own functioning.

For institutions that are vested with the responsibility of ensuring that all public authorities adhere to the RTI Act, it is alarming to note that in the seventeenth year of the implementation of the law, most ICs failed to provide complete information within the stipulated timeframe in response to information requests filed to them.

The legal requirement for the central and state ICs to submit annual reports every year to the Parliament and state legislatures respectively, is to make, among other things, their activities transparent and available for public scrutiny. Very few ICs fulfil this obligation and even fewer do it in time. Answerability of ICs to the Parliament, state legislatures and citizens is compromised when annual reports are not published and proactively disclosed every year, as required under the law.

Transparency is key to promoting peoples' trust in public institutions. By failing to disclose information on their functioning, ICs continue to evade real accountability to the people of the country whom they are supposed to serve. Unless ICs significantly improve their responsiveness to RTI applications, provide information proactively in the public domain through regularly updated websites and publish annual reports in a timely manner, they will not enjoy the confidence of people. The guardians of transparency need to be transparent and accountable themselves.

Agenda for Action to Enhance Transparency in the Working of ICs

- All ICs must put in place necessary mechanisms to ensure prompt and timely response to information requests filed to them.

- Each IC must ensure that relevant information about its functioning is displayed on its website. This must include information about the receipt and disposal of appeals and complaints, number of pending cases, and orders passed by ICs. The information should be updated in real time.

- ICs must ensure that, as legally required, they submit their annual report to the Parliament/state assemblies in a reasonable time. Violations should be treated as contempt of Parliament or state legislature, as appropriate. The Parliament and legislative assemblies should treat the submission of annual reports by ICs as an undertaking to the house and demand them accordingly. Annual reports published by ICs must also be made available on their respective websites.

- Appropriate governments should put in place a mechanism for online filing of RTI applications, along the lines of the web portal set up by the central government (rtionline.gov.in). Now the state governments of Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka and Delhi have also set up similar online portals. Further, the online portals should also provide facilities for electronic filing of first appeals and second appeals/complaints to the respective ICs.

Satark Nagrik Sangathan (SNS) is a citizens' group working to promote transparency and accountability in government functioning and to encourage active participation of citizens in governance. It is registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860 as Society for Citizens' Vigilance Initiative.

For further information, please visit: www.snsindia.org

[1] India's COVID-19 toll might be six times more than reported according to study, Indian Express, 8 January 2022,https://indianexpress.com/article/india/indias-covid-toll-may-be-6-times-more-than-reported-finds-study-7712387/).

[2] Peoples' Monitoring of the RTI Regime in India, 2011-2013' by RaaG & CES, 2014.

[3] Anjali Bhardwaj and others v. Union of India and others (Writ Petition No. 436 of 2018), https://indiankanoon.org/doc/47245795/.

[4] 'Report Card of Information Commissions in India', SNS & CES, 2020; 'Status of Information Commissions in India during Covid-19 Crisis', SNS & CES, May 2020; 'Report Card of Information Commissions in India', SNS & CES, 2019; 'Report Card of Information Commissions in India', SNS & CES, 2018; 'Tilting the Balance of Power - Adjudicating the RTI Act', RaaG, SNS & Rajpal, 2017; 'Peoples' Monitoring of the RTI Regime in India', 2011-2013, RaaG & CES, 2014; 'Safeguarding The Right To Information', RaaG & NCPRI, 2009. The reports are available at https://snsindia.org/rti-assessments/#IC2021.

[5] The Right to Information (Amendment) Act, 2019, https://dpiit.gov.in/rti/right-information-amendment-act-2019.

[6] NOTIFICATION, Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions (Department of Personnel and Training), New Delhi, 24 October 2019, http://documents.doptcirculars.nic.in/D2/D02rti/RTI_Rules_2019r4jr6.pdf.