- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- March 2023 - Volume 111

- Sabah's Stateless Issue: Navigating a Complex Legal Landscape for Basic Rights

FOCUS March 2023 Volume 111

Sabah's Stateless Issue: Navigating a Complex Legal Landscape for Basic Rights

Sabah, Malaysia, with its geographic location between Indonesia and the Philippines has contributed to the inflow of migrants into the country since its independence in 1957. Hence, the issue of statelessness in Sabah is unique and complex due to its migration history. In the 1970s, the state administration allowed Filipino refugees from Mindanao to seek refuge in Sabah,[1] when civil war broke out in southern Philippines.[2] The Sabah state administration sought the support of the federal government of Malaysia and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on the issue.[3] The federal government issued a special pass, currently known as "IMM13," an identification document that is also extended to the families of the refugees.[4] However, the state election in the mid-1980s led to change of the ruling political party which adopted a rigid and strict stance on the issue. The new government noted an increase of foreigners in the state which was seen as contributing to the rise in crimes and the reduction of employment opportunities for the locals.[5] Subsequently, when the situation improved in the Philippines, Filipinos who entered Sabah in 1985 were no longer considered refugees but economic migrants.[6] New documents were issued to people of Filipino descent in Sabah such as Kad Burung-Burung, under by Sabah Chief Minister's Department, and Sijil Banci by the Malaysian National Security Council (NSC).[7] Obtaining these documents is not a straightforward process and there are no clear and transparent guidelines that regulate applications. This can result in a person becoming stateless in Sabah.

Who Are the Stateless People?

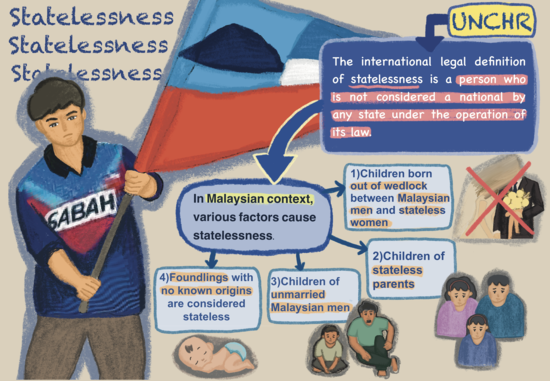

The international legal definition of statelessness is a person who is not considered a national by any state under the operation of its law.[8] In the Malaysian context, various factors cause statelessness. Children born out of wedlock between Malaysian men and stateless women, children of stateless parents, children of unmarried Malaysian men,[9] or foundlings with no known origins are considered stateless. Other stateless people came to Sabah, resided there for over forty years and were assimilated to the local culture and people but remained without any identity documentation.

Legal Questions

The identity documentation issue in Sabah is complex and the stateless communities are largely affected by these laws. Sabah has an extra step for late birth registration (registration of birth after forty-two days passed since birth). Late registration has to be applied for and needs the endorsement certificate issued under the discretion of the judges of Sabah. This rigid procedure is due to highly controversial issues of citizenship in Sabah.[10] However, this added challenge is not sufficiently justified as it robs children of their legal documents and their fundamental rights. At the same time, this is a policy of Sabah state. Families with generational statelessness are left with no access to legal identity and are punished by the state. There has been no legislative bill to address the issue. The path to naturalization for those who have been residing in Sabah for multiple generations is also unknown.

Current Situation

The stateless community continues to grow in Sabah due to lack of access to proper documentation both at the state and federal levels.[11] Based on the Department of Statistics Malaysia website, the 2020 Population and Housing Census shows that Sabah has a population of 3,398,948.[12] From that, an estimate of more than 810,000 are non-citizens, these include undocumented migrants and stateless persons. [13] The Home Ministry also reported in 2017 that Sabah had the largest number of stateless children or young adults. The National Registration Department's records reveal that there are 23,154 individuals under the age of 21 in Sabah who are stateless with at least one of their parents a Malaysian citizen.[14] However, these numbers do not seem to reflect the reality on the ground as not every stateless person has access to documentation application. The numbers are expected to be much higher than stated by the National Registration Department.

Moreover, local media recently have been highlighting the increase in number of children begging and glue-sniffing in the streets of Kota Kinabalu, Tawau, Sandakan and Lahad Datu. They have become prominent due to extreme poverty, as adults are unable to get proper employment, and eventually pushes children as young as six years old out on the street to earn money and fend for themselves. They are also at risk of being arrested by the authorities due to lack of identity documentation. In June 2022, more than one hundred beggars including children were arrested by enforcement agencies,[15] and sent to immigration detention centers. Moreover, human rights violations have reportedly occurred in these detention centers with overcrowded and poor living conditions.[16]

Possible Solutions

The Malaysian government has been working on initiatives to provide shelter for these children in order to take them off the street and also to hold their parents accountable.[17] But this is not effective since the core issue is still not being addressed: the communities of these children are stuck in a vicious cycle of poverty with no access to basic necessities. A recommendation has been made on enhancing transparency in the policies such as having clear and precise processes on the path to citizenship to reduce statelessness in Sabah. Under article 15A of the Federal Constitution, citizenship is granted at the discretion of the Minister of Home Affairs. However, there is no clarity on how these applications are being filtered by the Home Minister. Hence, establishing direct and clear processes will allow children applying under this procedure to fulfill the conditions.

Allowing stateless people to enjoy their basic rights such as right to healthcare, education, and employment is another issue. In terms of healthcare, the policy in the recent pandemic that no one should be left behind despite their documentation status is a good example. This allowed access to COVID-19 vaccine by everyone, including those not possessing identity documents.[18] This shows that the government's inclusive policy for the stateless communities is crucial at a time of healthcare crisis, and that it is not impossible for ministries to implement policies on reducing discrimination against stateless people.

Additionally, stateless children cannot also be denied the right to education. Children must be educated at all levels including kindergarten, primary and secondary levels. Fortunately, there are multiple communities and alternative learning centers that provide basic education for stateless children. These centers usually teach the three most important skills of reading, writing and counting. However, these classes are limited at the primary level. Those who are aiming to have a professional career will not have the opportunity to further their studies. In 2018, the education ministry did introduce the Zero Reject Policy to allow students with a Malaysian parent to enter public schools. However, this policy is currently not being enforced for stateless children.[19]

Stateless communities face various challenges when it comes to employment because of lack of proper documentation. Immigration Act 1955, Article 55B states that "Employing a person who is not in possession of a valid Pass" is an offense.[20] Hence, employers are liable to be fined and/or imprisoned for committing the offense of employing a stateless person. This risk inhibits employers from employing a person without proper documentation. At the same time, this situation deprives stateless people of their right to livelihood and forces them to take odd jobs that expose them to exploitation and abuse by employers.

The negative narrative and stigma around stateless communities perpetuated by the media cause the alienation of these communities,[21] creating a barrier for the public to empathize with the issue and understand their perspective. At the same time, stateless communities face discrimination. Shifting the behavior and mindset of the public is urgently needed to allow a change of perceptions and hopefully create an empathic community.

ANAK (Advocates for Non-discrimination and Access to Knowledge), a non-governmental organization (NGO) in Sabah, has been working to address this negative public mindset towards stateless and other disadvantaged children. It undertook various activities over the years, such as the following:

ANAK (Advocates for Non-discrimination and Access to Knowledge), a non-governmental organization (NGO) in Sabah, has been working to address this negative public mindset towards stateless and other disadvantaged children. It undertook various activities over the years, such as the following:

- Assistance in the enrolment of stateless children and facilitating voluntary repatriation of migrants;

- Assistance to undocumented/migrant children in accessing the vaccination program; and

- Successful support to citizenship applications.

ANAK, as an organization aiming to protect child rights regardless of documentation status, has collaborated with United Nations agencies, international organizations, local NGOs and communities in undertaking these services.

Aime Marisa Chong is a law student who is passionate about the issue of citizenship and migration. Fighting injustice and challenging the norms is what motivates her. This passion is reflected in her work with ANAK Sabah and Project Liber8 where she works on programs to empower migrant workers and advocate for equal citizenship rights. Her work with ANAK includes fighting for the basic rights of every child despite their documentation status and raising awareness of the issue of statelessness in Sabah. The fight for justice and equality will always be a part of Aime's journey, she believes that the right to a nationality should be a right, not a privilege. Depriving one of nationality would mean taking away her/his rights as a human being. Stephie Joseph Benedict is a Malaysian-Filipino who is passionate about the arts, culture and creativity. Her experience as child of a migrant and working with non-profit organization led her to do volunteer work in ANAK, while currently staying at home parenting and managing household. Mary Anne K. Baltazar has a Masters in Social Science and has fourteen years of experience in human rights and non-profit work. She is passionate about statelessness, migration and children's rights. She presented her paper for the Symposium of Young People against Slavery at the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Vatican City in 2014. In 2017, she was awarded a research grant by SHAPE-SEA for her research on Children at-Risk of Statelessness and their Constraints to Citizenship. She is currently a Fellow at the UMS-UNICEF Communications for Development Research Unit. She founded ANAK (Advocates for Non-discrimination and Access to Knowledge) to advocate for the rights of non-citizen children in Sabah.

Alanis Mah, an illustrator as well as a graphic designer, provided the illustration in this article. Since she was a little girl, she had passion for art as a hobby. She feels strongly about issues of citizenship and statelessness that she hopes to contribute in advocacy by using her artistic skills. She hopes that her artwork can serve as a source of inspiration for someone going through tough times. She believes that regardless of how life treats you, you must be brave. Always take a stand for yourself.

For further information, please contact: ANAK, ph: +60 14-280 7976; e-mail: anaksabahorg@gmail.com; Facebook page: www.facebook.com/anakkotakinabalu.

[1] Assim, Z., & Kassim, A., "Filipino Refugees in Sabah: State Responses, Public Stereotypes and the Dilemma Over Their Future," Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 47, No. 1, June 2009, https://kyoto-seas.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/470103.pdf.

[2] HURIGHTS OSAKA, "Mindanao Conflict: In Search of Peace and Human Rights," FOCUS Asia-Pacific, Volume 54, December 2008, www.hurights.or.jp/archives/focus/section2/2008/12/mindanao-conflict-in-search-of-peace-and-human-rights.html.

[3] Assim and Kassim, op. cit.

[4] Assim and Kassim, ibid.

[5] Yusoff, M. A., "Sabah Politics Under Pain," JATI - Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 6, 29-48, https://jati.um.edu.my/article/view/6739.

[6] Assim and Kassim, op. cit.

[7] FMT Reporters, Pemuda Warisan bimbang lebih ramai Pati "putihkan diri" mohon kad warga asing, Free Malaysia Today, 27 June 2022, www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/bahasa/tempatan/2022/06/27/pemuda-warisan-bimbang-lebih-ramai-pati-putihkan-diri-mohon-kad-warga-asing/.

[8] UNCHR (n.d.), About statelessness. UNCHR, www.unhcr.org/ibelong/about-statelessness/#:~:text=The%20international%20legal%20definition%20of.

[9] This is refers to children born out of wedlock of single Malaysian men and non-Malaysian women, and the children are left with the Malaysian father.

[10] Darell Leiking, Solve Sabah illegals first before late registrations, Malaysiakini, 18 April 2015, www.malaysiakini.com/news/295675.

[11] Malay Mail, Statelessness in Sabah in urgent need for lasting solution, says Suhakam, Daily Express, 19 April 2022, www.dailyexpress.com.my/news/191064/statelessness-in-sabah-in-urgent-need-for-lasting-solution-says-suhakam-/.

[12] DOSM, Population Clock by State, Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal, last update on 6 March 2023, www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=columnnew%2Fpopulationclock.

[13] Jamil A. Ghani, New National SDG Centre Can Resolve statelessness in Sabah, New Straits Times, 20 October 2022, www.nst.com.my/opinion/columnists/2022/10/842078/new-national-sdg-centre-can-resolve-statelessness-sabah.

[14] Bernie Yeo, "Kudos, Sabah!": Suhakam lauds state govt's temporary shelter for stateless children, Focus Malaysia, 30 November 2022, https://focusmalaysia.my/kudos-sabah-suhakam-lauds-state-govts-temporary-shelter-for-stateless-children/.

[15] Stephanie Lee, Sabah authorities nab over 100 beggars, The Star, 30 June 2022, www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2022/06/30/sabah-authorities-nab-over-100-beggars.

[16] FMT Reporters, Indonesian NGOs rebuke Saifuddin over "unethical" remarks on treatment of migrants, Free Malaysia Today, 11 December 2022, www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2022/12/11/indonesian-ngos-rebuke-saifuddin-over-unethical-remarks-on-treatment-of-migrants/.

[17] Stephanie Lee, Sabah to set up protection centre to rescue child beggars, The Star, 28 November 2022, www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2022/11/28/sabah-to-set-up-protection-centre-to-rescue-child-beggars.

[18] Azreen Hani, More than 1m stateless individuals completed their Covid-19 vaccination, The Malaysian Reserve, 7 October 2021, https://themalaysianreserve.com/2021/10/07/more-than-1m-stateless-individuals-completed-their-covid-19-vaccination/.

[19] FMT Reporters, Putrajaya not following policy on education for all children, group laments, Free Malaysia Today, 2 March 2022, www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2022/03/02/putrajaya-not-following-policy-on-education-for-all-children-group-laments/.

[20] The Act 155 Immigration Act 1959/63.

[21] More than 1.3 mil non-M'sians in Sabah: Don, Daily Express, 21 July 2017, www.dailyexpress.com.my/news.cfm?NewsID=118979.