- TOP

- 資料館

- FOCUS

- December 2023 - Volume 114

- The National Human Rights Commission of Korea and the Efforts of Civil Society to Secure Its Independence

FOCUS December 2023 Volume 114

The National Human Rights Commission of Korea and the Efforts of Civil Society to Secure Its Independence

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Paris Principles on the Status of the National Human Rights Institutions. The Paris Principles set out the main criteria that a national human rights institution (NHRI) is required to meet - establishment by law, a broad mandate, independence, pluralism and adequate resources. Meeting these criteria in the process of establishing such an institution in Korea and afterwards maintaining it especially in preventing it from being under government control were a struggle.

The demand to establish an NHRI in Korea was raised first by the civil society in 1993. Many Korean human rights lawyers and civil society organization (CSO) leaders, who were preparing to attend the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, proposed to the government to establish such an institution. After many decades of harsh military dictatorship, Korea was finally enjoying a hard-won democracy, full of hope for a society where human rights should and would be respected and protected. The momentum was ripe during the presidential election in December 1997. The front-runner Kim Dae Jung promised to establish an NHRI if he would be elected as President. It took four more years to finally establish the institution in 2001, but had only a certain level of independence.

In September 1998, the newly inaugurated government announced the draft "Human Rights Law." The bill though was deeply disturbing: The status of the National Human Rights Commission was envisaged as a "special legal entity" under the control of the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). In the composition of NHRCK, out of a total of eleven Commissioners, four ex-officio members would be the deputy ministers of relevant ministries and the rest seven members would be appointed by the President upon the recommendations of MoJ. It was a betrayal of the essential prerequisite of an independent NHRI. This bill was then speedily approved by the Cabinet in March 1999 and sent to the National Assembly in following month (April) for its enactment.

The civil society had to move quickly and decisively. Already, about thirty CSOs had formed a Joint Action Committee to promote the establishment of NHRI. In response to the MoJ's bill, this Committee was re-organized in April 1999, its membership was expanded to include as many as seventy CSOs, and was renamed Joint Counter-Measure Committee to demand that the government establish a "proper NHRI." To block the government-proposed bill, thirty-four human rights leaders started fasting in front of Myeongdong Cathedral, a symbolic place that functioned as the center of democracy movement.

The Joint Counter-Measure Committee held so many emergency meetings to strategize how to deal with the changing political situations and the evolving versions of the bill, which kept getting revised while the negotiations in the parliament and between the political parties and the government were going on. The civil society also invited an expert from Australia and had public discussions at an open forum.

All these serious efforts paid off. In April 2001, the National Human Rights Commission Act was passed, with one hundred thirty-seven votes in favor, one hundred thirty-three votes against it and three abstentions. It was established as a state organ, without being under the power of any of the Executive, Legislative or Judicial institutions. The National Human Rights Commission Act, in its Article 3, paragraph 2, provides that the Commission shall "independently perform tasks within its authority." Ideally, the Commission would be best if established as an independent organ by constitutional amendment, which was not possible. Therefore, the next best way was to establish it by legislation.

Finally, on 25 November 2001, the National Human Rights Commission of the Republic of Korea (NHRCK) was established. The NHRCK can function independently, and the decisions are to be made by eleven Commissioners - four standing (full-time) and seven non-standing members. They are selected through three different routes: The National Assembly elects four Commissioners (including two standing members); the President of the Republic of Korea appoints another four Commissioners (including the NHRCK President and one standing member); and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court recommends the remaining three Commissioners. The Commissioners serve for three years and may be reappointed only once. In accordance with the demands of women's organizations, more than four Commissioners should be female, which later was revised to "a specific gender should not exceed" six Commissioners. These are unique features of the NHRCK, concluded after a series of negotiations. In other countries, the composition and terms of office of the Commissioners and how they are elected/appointed vary a great deal.

During its early days, the NHRCK enjoyed a very high social reputation and respect. The NHRCK's first President was a well-known and very respected human rights lawyer who fought against the dictatorship. On the NHRCK's opening day, people lined up in front of its Counselling Center to register their complaints as the first cases.

In the course of twenty years, the NHRCK's staff was increased from one hundred eighty to two hundred forty eight, but the number of personnel has been strictly under the control of the Ministry of the Interior and Safety (MoIS). Likewise, the NHRCK does not have autonomy in its budget allocation, which is controlled by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MoEF). In 2021, the NHRCK tried to amend the National Finance Act, so that the NHRCK's status could be elevated from a "central government agency" to an "independent institution" similar to the status of the National Election Commission. The National Finance Act prescribes that the government (i.e., MoEF) should respect the opinion of (and when financial adjustment is required, consult with) the head of the "independent institution." The NHRCK's attempt, however, failed, due to opposition from the government. Therefore, the budget and personnel are still under the tight control of MoEF and MoIS respectively.

Thus far, there have been three big occasions that the independent functioning of the NHRCK was put under risk. The first moment of danger was in January 2008 when the government switched hands from the progressives to the conservatives. The Presidential Transition Committee announced that the new government would change its structure, and the NHRCK would be put directly under President Lee Myung-bak. At that time, I was serving as a non-standing member of the NHRCK. I happened to be in Geneva, attending the regular session of the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). I alerted the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). I requested the OHCHR to swiftly react to this attempt to undermine the independence of the NHRCK. Then High Commissioner Louise Arbour sent a letter of serious concern to the Transition Committee, which was widely reported by the media. Together with warnings and worries from the international human rights community, it helped to stop the government attempt.

The Lee government, however, was determined to weaken the power of NHRCK. In the following year the second crisis came. The Board of Audit and Inspection released the results of inspection, announcing that the NHRCK needed to reorganize its system to be more efficient. In April 2009, forty-four personnel of NHRCK were dismissed, which was equal to 21.2 percent of the total number of personnel. In addition, the organizational structure was reduced to almost half. Under this situation, the NHRCK's President submitted his resignation four months earlier than the expiration of his term.

An additional blow resulted in a long-term crisis to the NHRCK. President Lee appointed a non-human rights person as the NHRCK's new head. The civil society and human rights organizations protested this appointment and stopped to cooperate with the NHRCK. Three NHRCK Commissioners resigned in November 2010. In 2011, the NHRCK did not renew the employment contract of a leader of its employees' trade union. Eleven staff members who protested were sanctioned. Despite all the turmoil, the NHRCK's President was reappointed in August 2012 for his second term. For six years, the NHRCK did not function properly. The accreditation of NHRCK by the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI) was withheld three times. NHRCK regained its "A status" back only in 2016.

The NHRCK is not a judicial organ. Only when it is perceived by the public as an independent institution, can it function properly. Only when the NHRCK earns and enjoys the respect would its policy recommendations and decisions on complaints become authoritative, and the relevant stakeholders would respect and implement them.

In the early days of its existence, half of the complaints submitted to the NHRCK came from prisons and detention centers. Easy accessibility and dedication of the staff members made the NHRCK a reliable national institution that people could trust and turn to for help. Currently with its five regional offices established across Korea, the NHRCK received 10,573 cases in 2022. Still the highest number of complaints on alleged human rights violations comes from the prisons, constituting about 20 percent of the total number of complaints, followed by complaints against the prosecutors, as well as the protective facilities where many people are institutionalized. The NHRCK issues policy recommendations frequently; in 2022 it issued thirty-three resolutions with an acceptance rate of 86.9 percent. All policy recommendations and other documents are uploaded to the NHRCK's website, www.humanrights.go.kr.

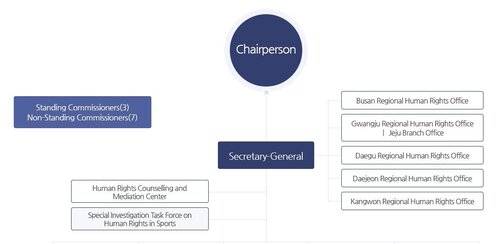

NHRCK organizational structure (NHRCK website, January 2024)

NHRCK organizational structure (NHRCK website, January 2024)

Though enjoying an "A" status, the NHRCK has a long way to go until it satisfies all the criteria of the Paris Principles. Continued efforts by the Korean society will shorten the way towards a truly independent NHRCK.

It will be a dream-come-true situation if an independent NHRI would be established in Japan. Together with Korean NHRI, the Japanese NHRI can make efforts to promote and protect human rights in Asia, where there is yet no regional human rights mechanism.

Heisoo Shin is the Chairperson of the Board of Directors of the Korea Center for United Nations Human Rights Policy.

For further information, please contact: Heisoo Shin, Korea Center for United Nations Human Rights Policy, Rm. 1058, #100 Cheonggyecheon-ro, Jung-gu, (Supyo-dong, Signature Tower, West) Seoul, 04542, Republic of Korea, e-mail: kocun@kocun.org, https://kocun.org.

Note:

This is an edited version of the speech delivered during the International Symposium Commemorating the 8th Anniversary of the adoption of SDGs - To Establish a National Human Rights Institution in Japan and implement international human rights standards! held n Osaka, Japan on 10 September 2023.